3. Unsettled Science, Failed Climate Modeling (161)

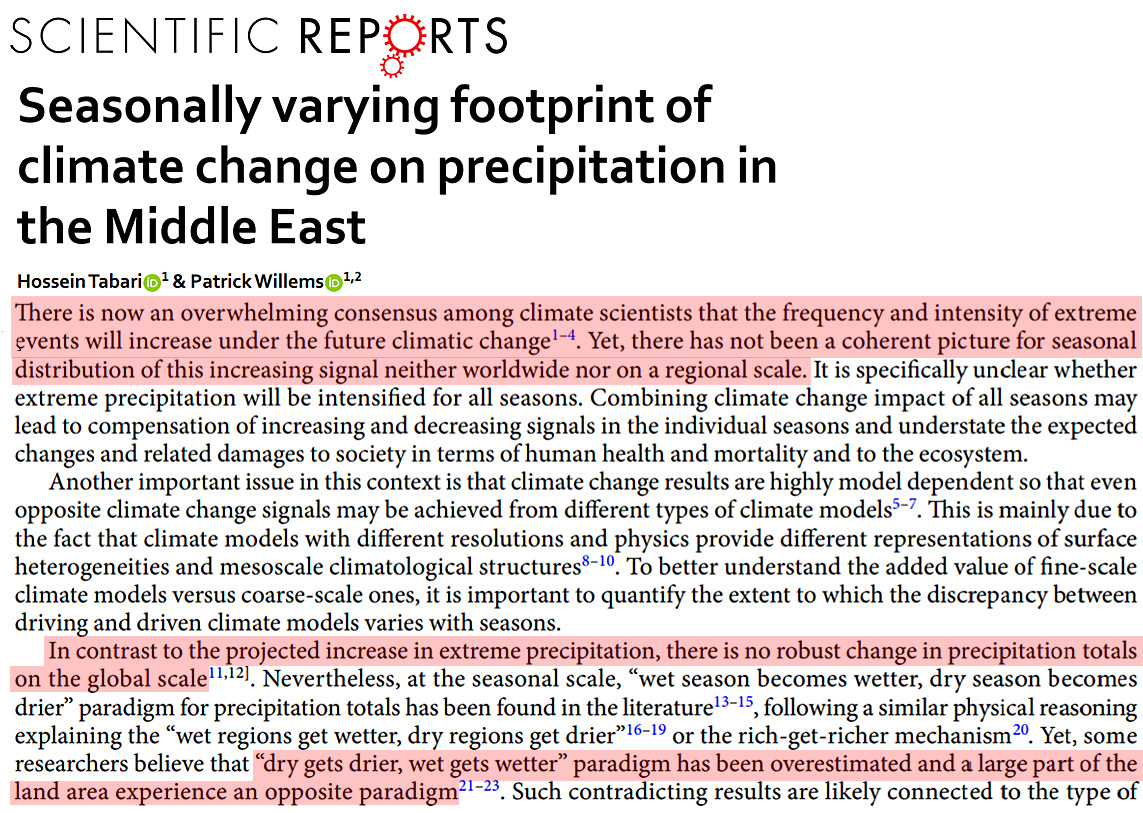

Climate Model Unreliability/Biases/Errors (27)

Urban Heat Island: Raising Surface Temperatures Artificially (5)

Failing Renewable Energy, Climate Policies (18)

Wind Power Harming The Environment, Biosphere (19)

Elevated CO2: Greens Planet, Higher Crop Yields (20)

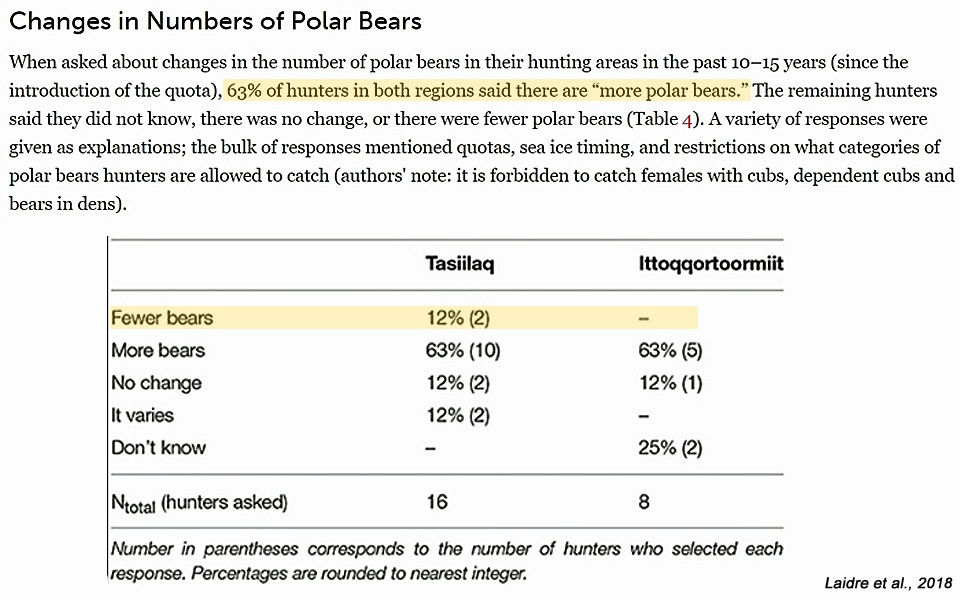

Polar Bear (and other) Populations Not Decreasing (10)

Global Warming Saves Lives. Cold Kills. (9)

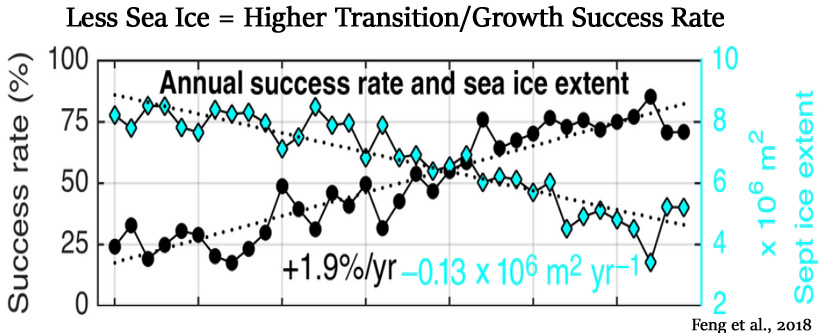

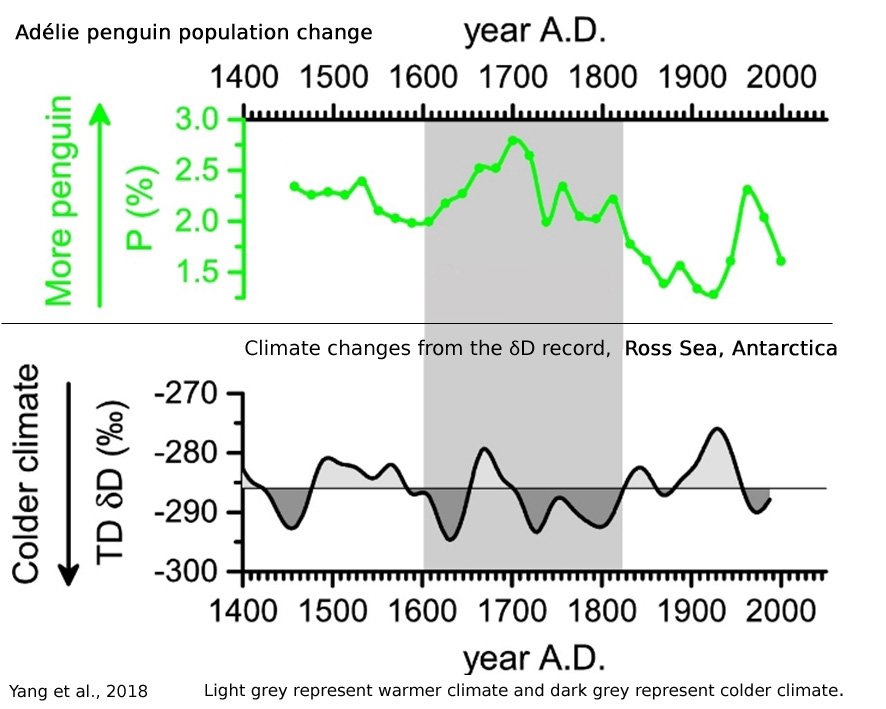

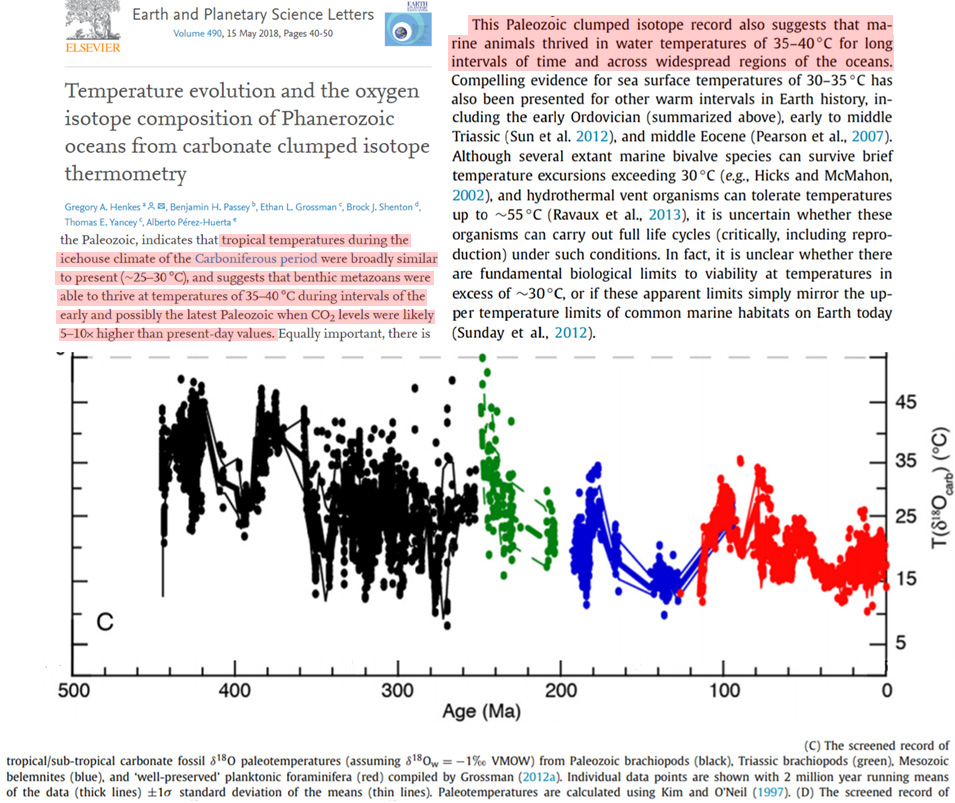

Warming, Acidification Not Harming Oceanic Biosphere (11)

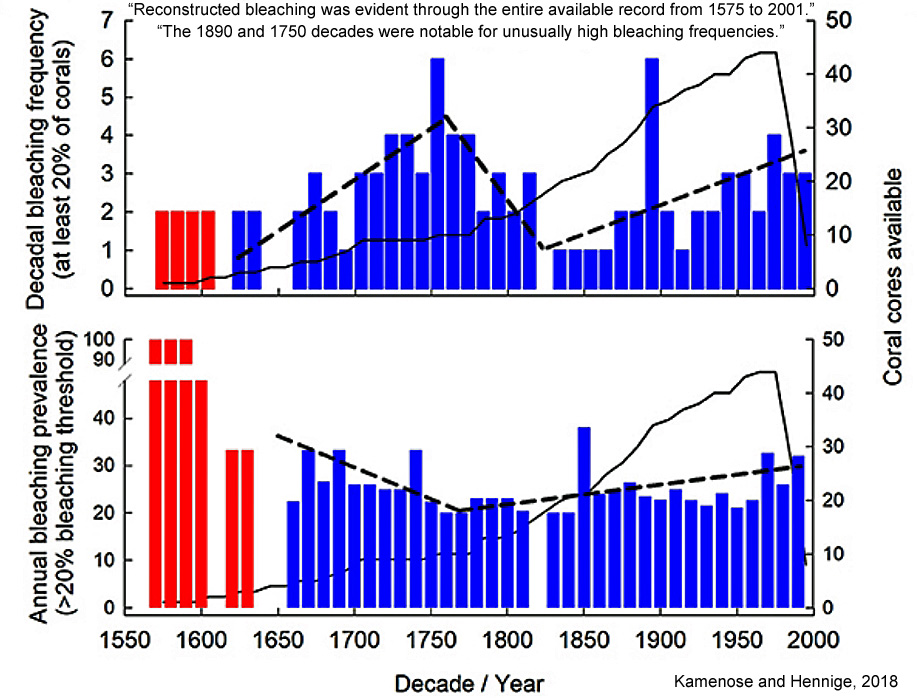

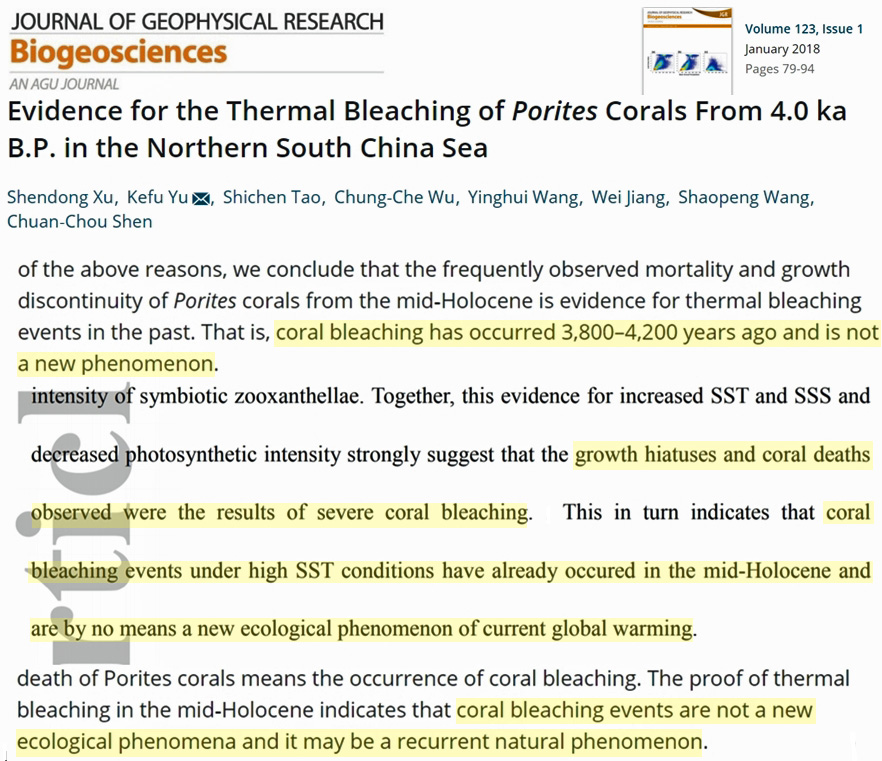

Coral Bleaching Is A Natural, Non-Anthropogenic Phenomenon (2)

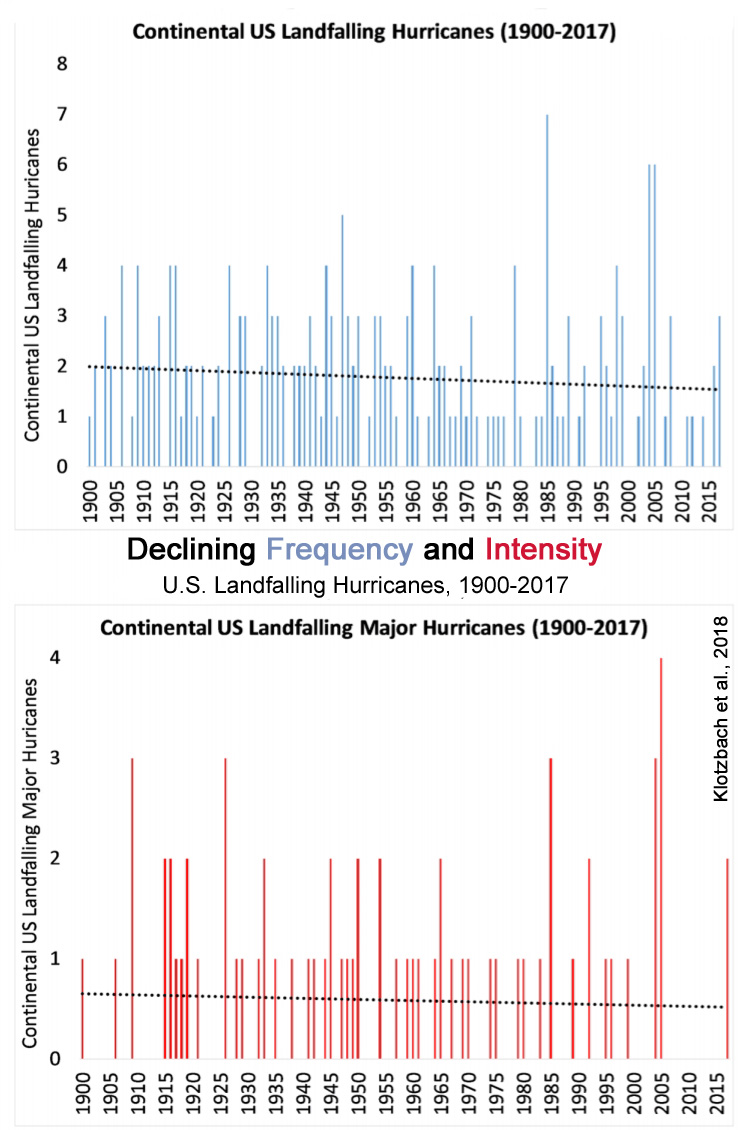

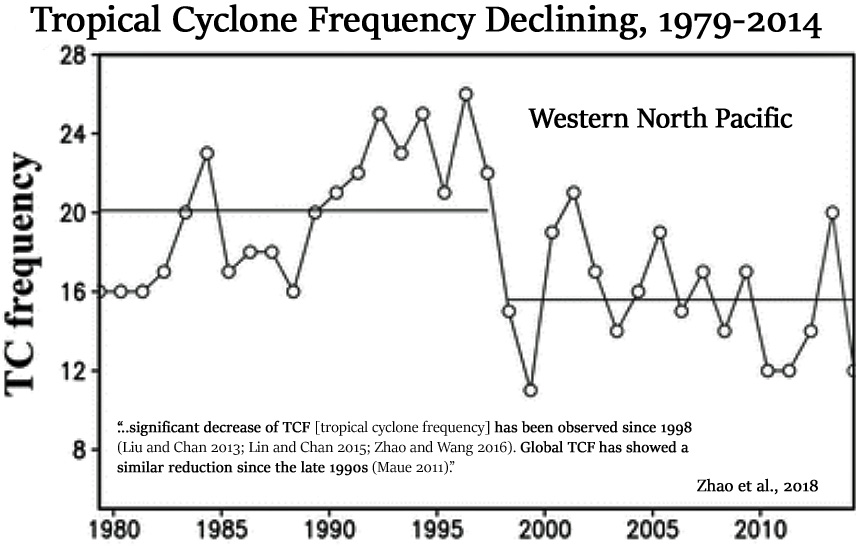

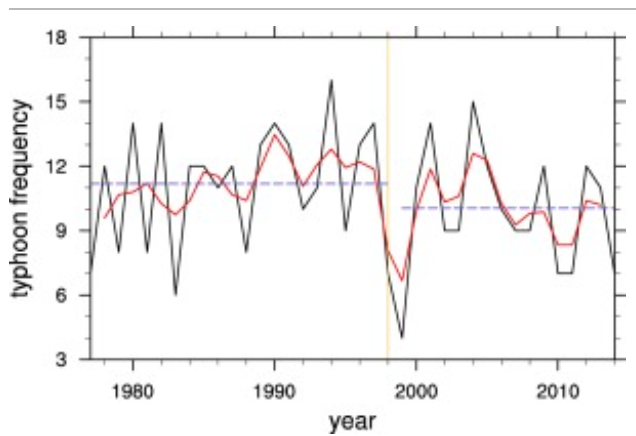

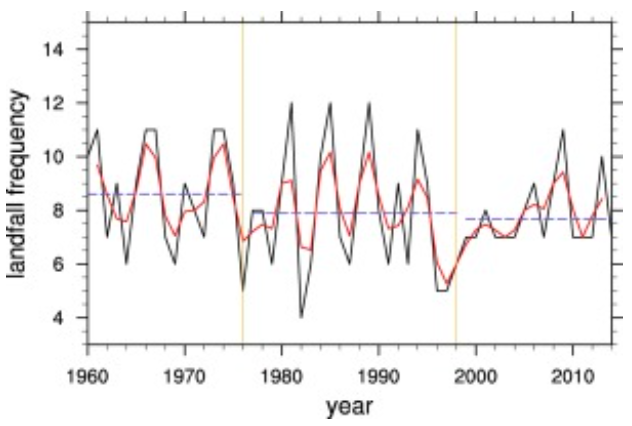

No Increasing Trends In Intense Hurricanes/Storms (8)

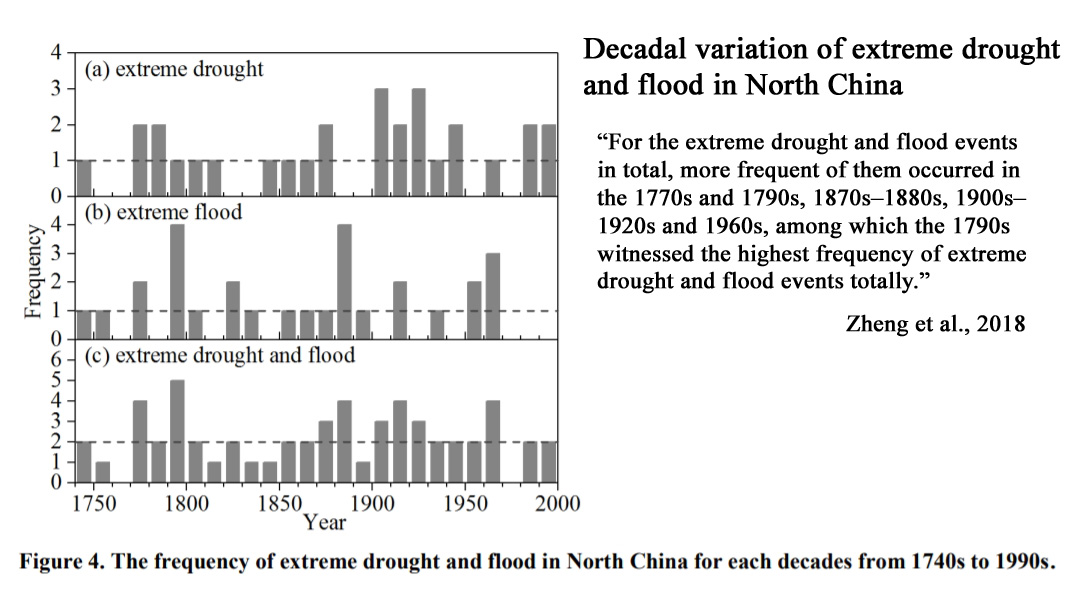

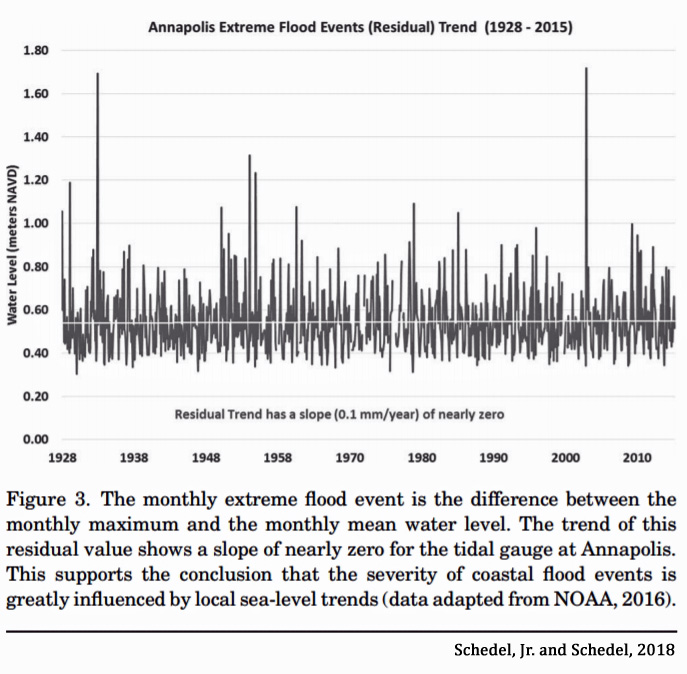

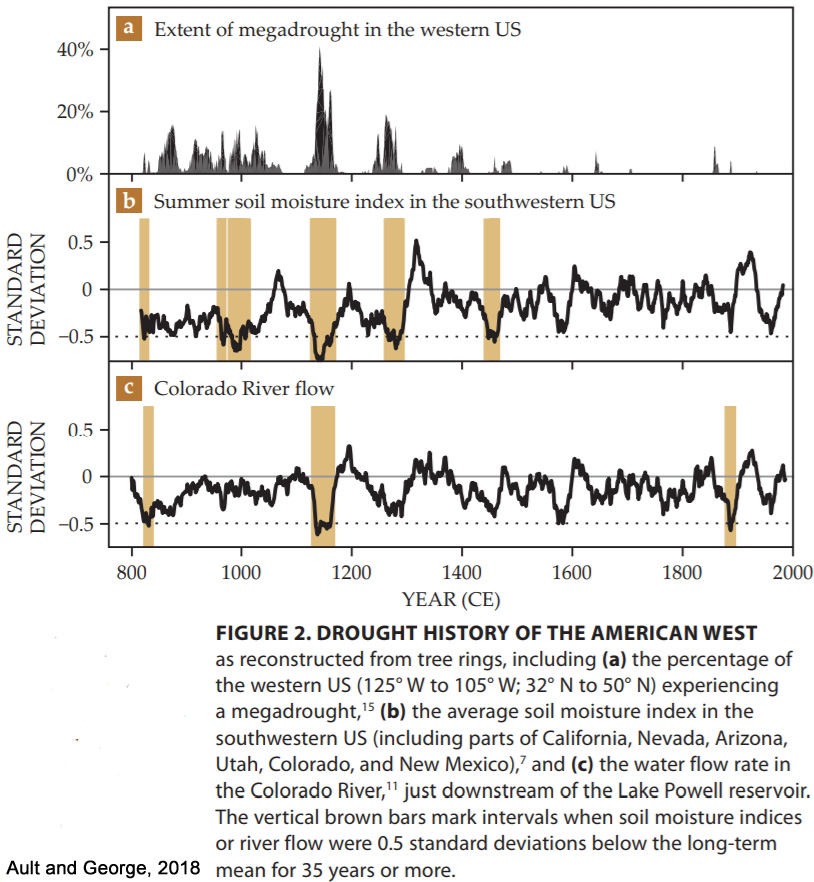

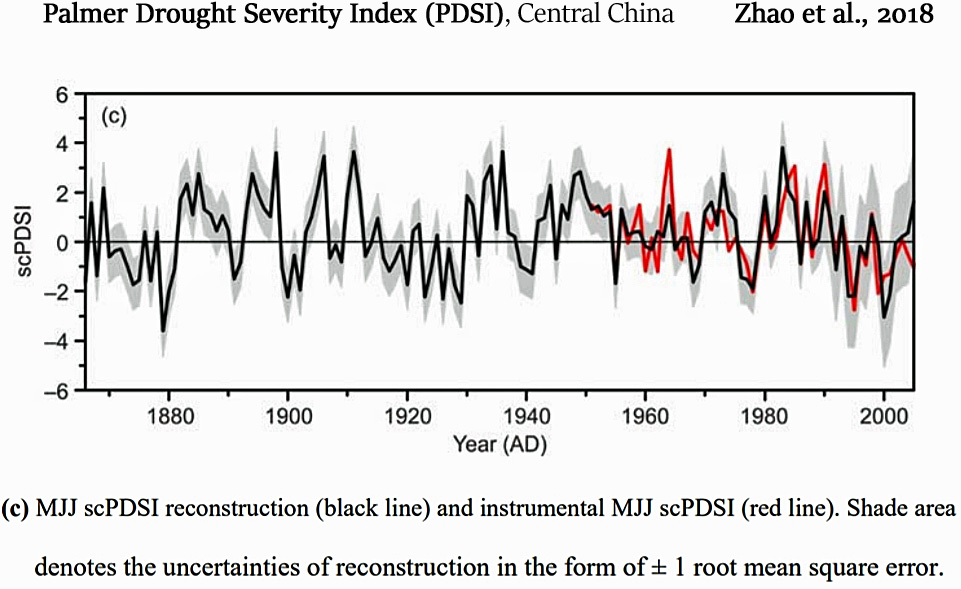

No Increasing Trend In Drought/Flood Frequency, Severity (7)

Natural CO2 Emissions A Net Source, Not A Net Sink (5)

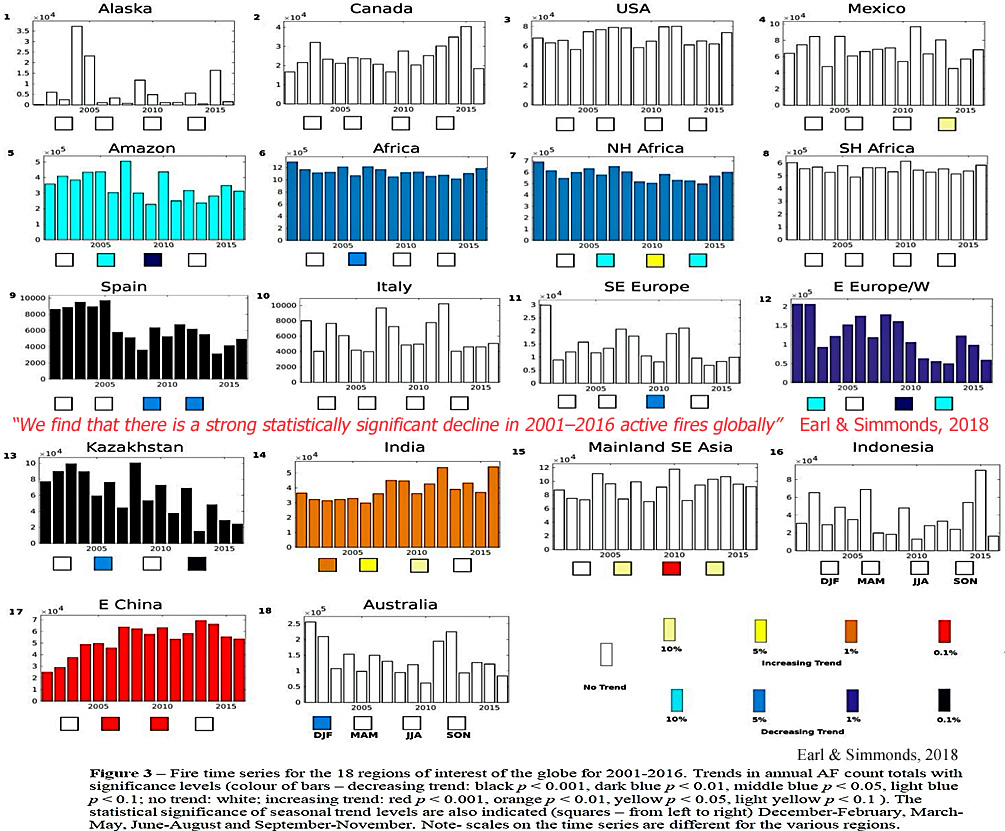

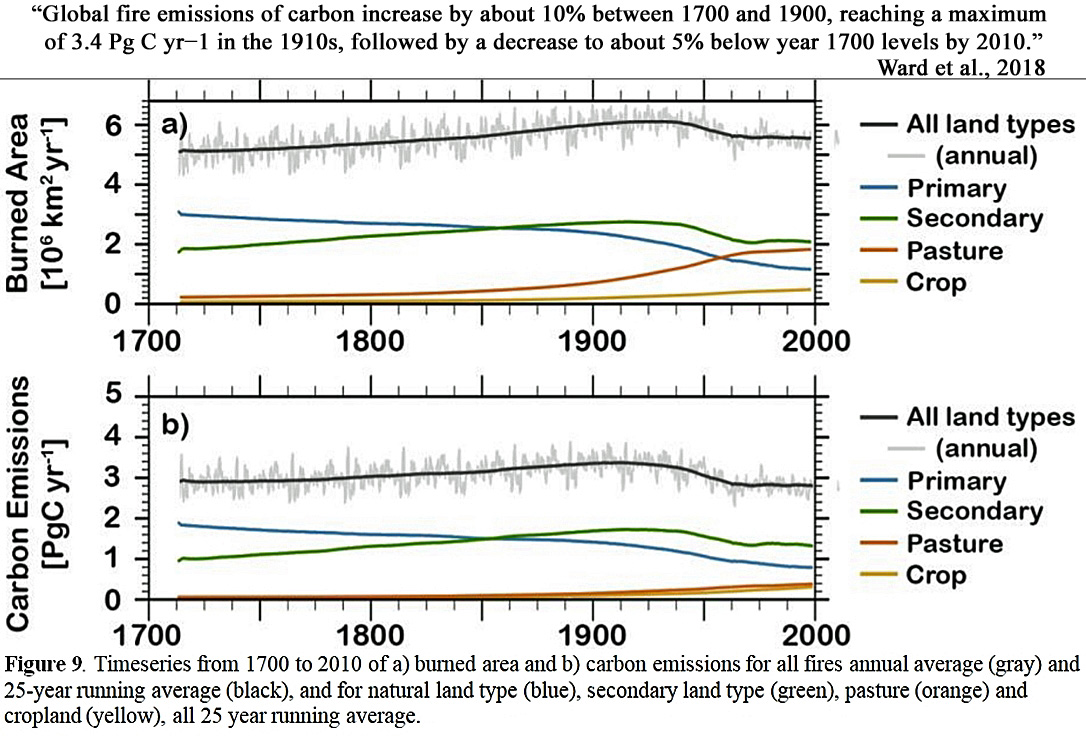

Global Fire Frequency Declining As CO2 Rises (2)

CO2 Changes Lag Temperature Changes By 1000+ Years (3)

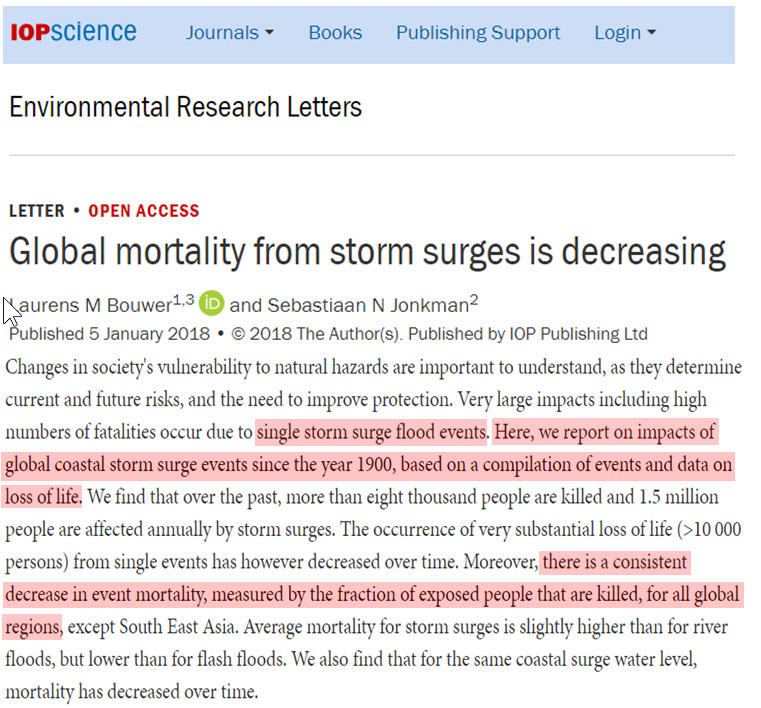

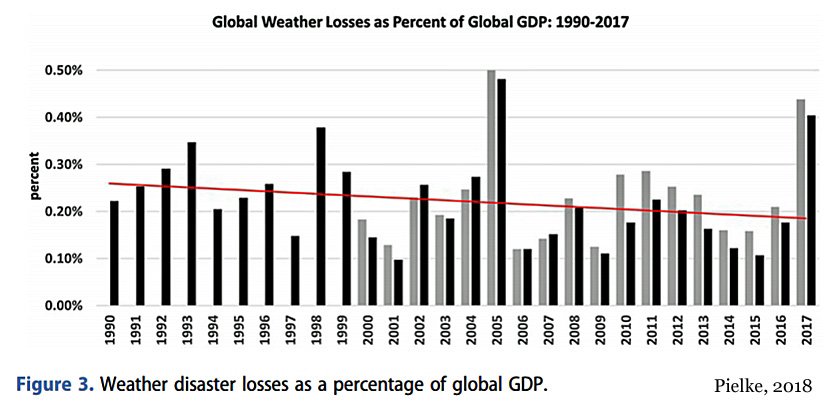

Global Losses/Deaths From Weather Disasters Declining (2)

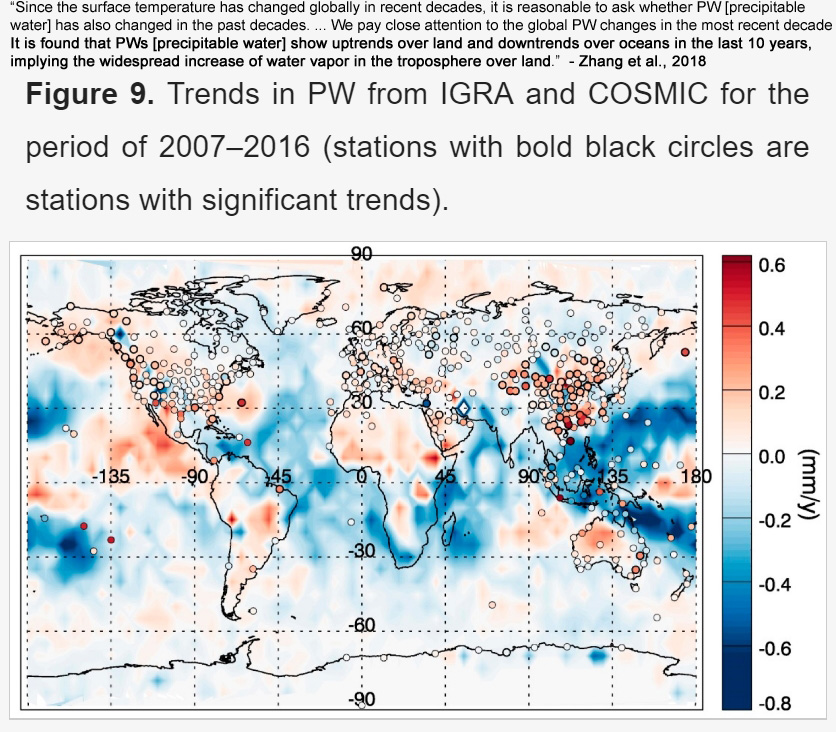

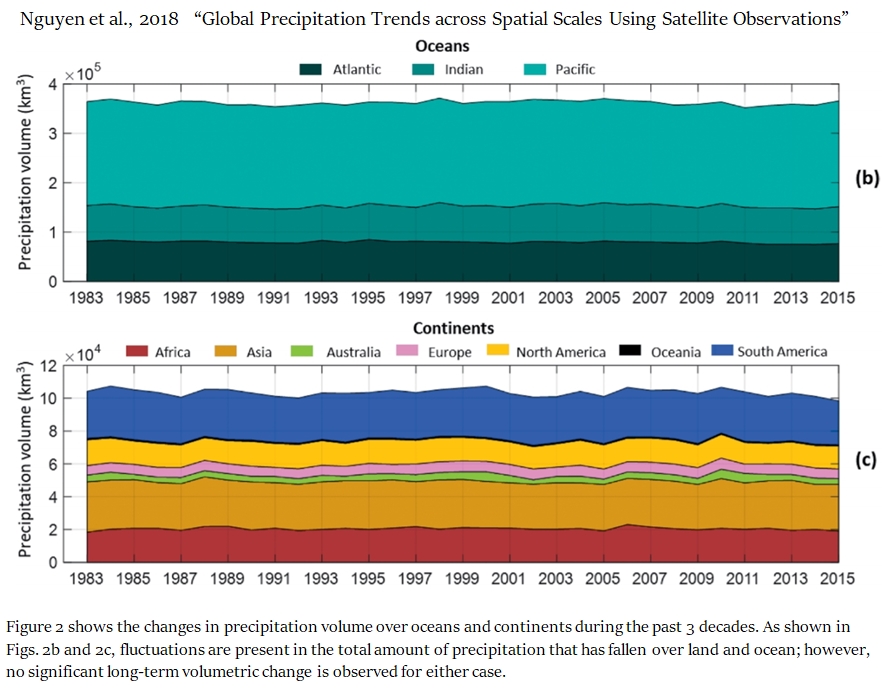

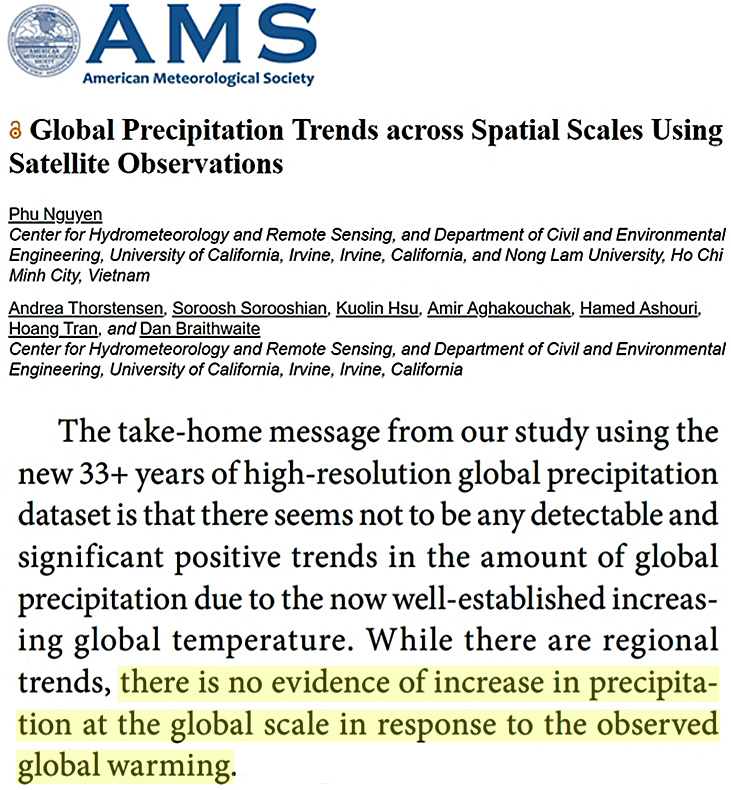

No AGW Changes To Hydrological Cycle Detectable (6)

Peak Oil As Myth (3)

Miscellaneous (16)

Climate Model Unreliability/Biases/Errors

Collins et al., 2018 Here there is a dynamical gap in our understanding. While we have conceptual models of how weather systems form and can predict their evolution over days to weeks, we do not have theories that can adequately explain the reasons for an extreme cold or warm, or wet or dry, winter at continental scales. More importantly, we do not have the ability to credibly predict such states. Likewise, we can build and run complex models of the Earth system, but we do not have adequate enough understanding of the processes and mechanisms to be able to quantitatively evaluate the predictions and projections they produce, or to understand why different models give different answers. … The global warming ‘hiatus’ provides an example of a climate event potentially related to inter-basin teleconnections. While decadal climate variations are expected, the magnitude of the recent event was unforeseen. A decadal period of intensified trade winds in the Pacific and cooler sea surface temperatures (SSTs) has been identified as a leading candidate mechanism for the global slowdown in warming.

Shen et al., 2018 The results showed that both future climate change (precipitation and temperature) and hydrological response predicted by the twenty GCMs [climate models] were highly uncertain, and the uncertainty increased significantly over time. For example, the change of mean annual precipitation increased from 1.4% in 2021–2050 to 6.5% in 2071–2100 for RCP4.5 in terms of the median value of multi-models, but the projected uncertainty reached 21.7% in 2021–2050 and 25.1% in 2071–2100 for RCP4.5.

Christy et al., 2018 [A]s new versions of the datasets are produced, trend magnitudes have changed markedly, for example the central estimate of the global trend of the mid-troposphere in Remote Sensing System’s increased 60% from +0.078 to +0.125°C decade−1, between consecutive versions 3.3 and 4.0 (Mears and Wentz 2016). … As an experiment, Mears et al. recalculated the RSS overall trend by simply truncating NOAA-14 data after 1999 (which reduced their long-term trend by 0.02 K decade−1). However, this does not address the problem that the trends of the entire NOAA-12 and −14 time series (i.e. pre-2000) are likely too positive and thus still affect the entire time series. Additionally, the evidence from the Australian and U.S. VIZ comparisons support the hypothesis that RSS contains extra warming (due to NOAA-12, −14 warming.) Overall then, this analysis suggests spurious warming in the central estimate trend of RSS of at least +0.04°C decade−1, which is consistent with results shown later based on other independent constructions for the tropical belt. … When examining all of the evidence presented here, i.e. the correlations, magnitude of errors and trend comparisons, the general conclusion is that UAH data tend to agree with (a) both unadjusted and adjusted IGRA radiosondes, (b) independently homogenized radiosonde datasets and (c) Reanalyses at a higher level, sometimes significantly so, than the other three [NOAA, RSS, UW]. … One key result here is that substantial evidence exists to show that the processed data from NOAA-12 and −14 (operating in the 1990s) were affected by spurious warming that impacted the four datasets, with UAH the least affected due to its unique merging process. RSS, NOAA and UW show considerably more warming in this period than UAH and more than the US VIZ and Australian radiosondes for the period in which the radiosonde instrumentation did not change. … [W]e estimate the global TMT trend is +0.10 ± 0.03°C decade−1. … The rate of observed warming since 1979 for the tropical atmospheric TMT layer, which we calculate also as +0.10 ± 0.03°C decade−1, is significantly less than the average of that generated by the IPCC AR5 climate model simulations. Because the model trends are on average highly significantly more positive and with a pattern in which their warmest feature appears in the latent-heat release region of the atmosphere, we would hypothesize that a misrepresentation of the basic model physics of the tropical hydrologic cycle (i.e. water vapour, precipitation physics and cloud feedbacks) is a likely candidate.

Abbott and Marohasy, 2018 While general circulation models are used by meteorological agencies around the world for rainfall forecasting, they do not generally perform well at forecasting medium-term rainfall, despite substantial efforts to enhance performance over many years. These are the same models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to forecast climate change over decades. Though recent studies suggest ANNs [artificial neural networks] have considerable application here, including to evaluate natural versus climate change over millennia, and also to better understand equilibrium climate sensitivity.

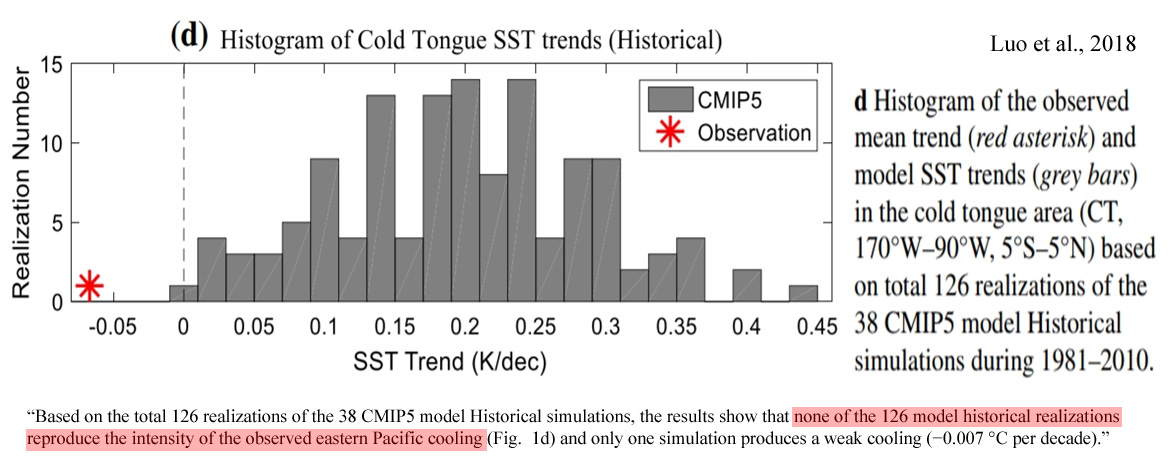

Luo et al., 2018 Over the recent three decades sea surface temperate (SST) in the eastern equatorial Pacific has decreased, which helps reduce the rate of global warming. However, most CMIP5 model simulations with historical radiative forcing do not reproduce this Pacific La Niña-like cooling. Based on the assumption of “perfect” models, previous studies have suggested that errors in simulated internal climate variations and/or external radiative forcing may cause the discrepancy between the multi-model simulations and the observation…. Based on the total 126 realizations of the 38 CMIP5 model Historical simulations, the results show that none of the 126 model historical realizations reproduce the intensity of the observed eastern Pacific cooling (Fig. 1d) and only one simulation produces a weak cooling (−0.007 °C per decade).

Ding et al., 2018 [W]e find that there was a warming hiatus/slowdown since 2005 at Ny-Ålesund. Additionally, the variation of air temperature lags by 8–9 years, which implies that the warming hiatus probably exists in the Arctic but lags behind, globally. This phenomenon is not an isolated instance, An et al. [2017] reported that the warming rate above 4000 m of the Tibetan Plateau has been slowing since the mid-2000s. In the Antarctic Peninsula, the slowdown of the increasing temperature trend was also found after 1998/1999, however, the reason is attributed to local phenomena, such as the deepening of Amundsen Sea Low and not due to the global hiatus [Turner et al., 2016]. … From the correlation analysis, we found Ny-Ålesund could represent most Arctic areas, especially the Atlantic-Arctic sector. … Especially air temperature, the record of Ny-Ålesund can capture the variation of surface temperature over most of [the] Arctic. … The oscillations of atmospheric dynamic systems, the methods of energy transport from low to high latitudes, and feedback mechanisms of the Arctic on climate change may contribute to the warming hiatus. … [C]limate changes in polar areas remain difficult to predict, which indicates that the underlying mechanisms of polar amplification remain uncertain and debatable.

Lacour et al., 2018 The representation of clouds over Greenland is a central concern for the models because clouds impact ice-sheet surface melt. We find that over Greenland, most of the models have insufficient cloud cover during summer. In addition, all models create too few non-opaque liquid containing clouds optically thin enough to let direct solar radiation reach the surface (-1% to -3.5% at the ground level). Some models create too few opaque clouds. In most climate models, the cloud properties biases identified over all Greenland also apply at Summit proving the value of the ground observatory in model evaluation. … At Summit, climate models underestimate cloud radiative effect (CRE) at the surface, especially in summer. The primary driver of the summer CRE biases compared to observations is the underestimation of the cloud cover in summer (-46% to -21%), which leads to an underestimated longwave radiative warming effect (CRELW = -35.7 W m-2 to -13.6 W m-2 compared to the ground observations) and an underestimated shortwave cooling effect (CRESW = +1.5 W m-2 to +10.5 W m-2 compared to the ground observations). Overall, the simulated [modeled] clouds do not radiatively warm the surface as much as observed. … Of particular importance, clouds can trigger surface melt over a large portion of the Greenland Ice Sheet (Bennartz et al. 2013; Solomon et al. 2017). Greenland surface melting increases non-linearly with increasing temperatures due to positive feedbacks between cloud microphysics, surface melting and surface albedo (Fettweis et al. 2013) and modulates the ice sheet mass balance (Van Tricht et al. 2016; Hofer et al. 2017). … Every model included in this study underestimates the net cloud radiative surface warming in summer. … [O]nly few general circulation models are able to represent the surface of the Greenland ice sheet (Cullather et al. 2014). … Since the overall cloud radiative warming is underestimated in the models, we may expect an underestimate of Greenland surface melting. However, misrepresentation of clouds is not the only contributor to biases in the modeled surface melting.

Guo et al., 2018 The snow‐albedo feedback is a crucial component in high‐altitude cryospheric change but is poorly quantified over the Third Pole, encompassing the Karakoram and Tibetan Plateau. … [I]t is noteworthy that the magnitude of the constrained strength is only half of the unconstrained model estimate for the Third Pole, suggesting that current climate models generally overestimate the feedback of spring snow change to temperature change based on the unmitigated scenario.

Kravtsov et al., 2018 D]eviations of the model-simulated climate change from observations, such as a recent “pause” in global warming, have received considerable attention. Such decadal mismatches between model-simulated and observed climate trends are common throughout the twentieth century, and their causes are still poorly understood. While climate models exhibit various levels of decadal climate variability and some regional similarities to observations, none of the model simulations considered match the observed signal in terms of its magnitude, spatial patterns and their sequential time development. These results highlight a substantial degree of uncertainty in our interpretation of the observed climate change using current generation of climate models.

Essex and Tsonis, 2018 Climate models do not and cannot employ known physics fully. Thus, they are falsified, a priori. Incomplete physics and the finite representation of computers can induce false instabilities. … [A[re there propositions that contemporary models make, crucial to their own objectives, that are falsifiable? Is there any physical test possible that would force us to conclude that they are unable to achieve their own objectives, thus requiring a rethinking of basic assumptions? This paper addresses this question. But it is a question that cannot be comprehended in the face of many widely-held misconceptions about the direct meteorologically based projection modeling of climate. Foremost among these misconceptions is that climate models are full implementations of known, mature physics. This false conception can lead to the conclusion that falsification is irrelevant because models are simply an execution of previously known correct physics. … The empirical nature of large climate models can be clearly seen in their diverse outputs. If they followed the laws of physics in their entirety, they would all produce the same results under the same conditions. But they do not. In a recent study, the Climate Model Inter-comparison Project phase 3 (CMIP3) models [2] were considered and a detailed comparison at the dynamics level, using an approach involving climate networks [Steinhaeuser and Tsonis, 2013] was performed. It was found that the models not only don’t agree with each other when it comes to dynamics, they also don’t agree with reality.

Kam et al., 2018 In summary, there is marginal evidence for an emerging detectable anthropogenic contribution toward earlier WSCT [winter-spring center time] in parts of North America. The regions with strongest relative indication of an anthropogenic contribution in our analysis include: the north-central U.S. (Region 3); the mountainous western U.S./southwestern Canada (Region 1); and extreme northeastern U.S. and Canadian Maritimes (Region 6). However, in none of the regions examined do a majority of the nine CMIP5 models examined robustly support a detectable attribution of an earlier (decreasing) WSCT trend to anthropogenic forcing. At some level, the difficulty in detecting a climate change signal comes down to low signal to noise ratio (Ziegler et al. 2005). Apparently, for the variable at hand, the climate change influence is not very large compared to interannual/interdecadal variability noise.

Bracegirdle et al., 2018 Our results show that the observed peak in multidecadal jet strength variability is even more unusual than NAO variability when compared to the model‐simulated range across 133 historical CMIP5 simulations. Some CMIP5 models appear capable of reproducing the observed low‐frequency peak in jet strength, but there are too few simulations of each model to clearly identify which.

Scafetta et al., 2018 The period from 2000 to 2016 shows a modest warming trend that the advocates of the anthropogenic global warming theory have labeled as the “pause” or “hiatus.” These labels were chosen to indicate that the observed temperature standstill period results from an unforced internal fluctuation of the climate (e.g. by heat uptake of the deep ocean) that the computer climate models are claimed to occasionally reproduce without contradicting the anthropogenic global warming theory (AGWT) paradigm. In part 1 of this work, it was shown that the statistical analysis rejects such labels with a 95% confidence because the standstill period has lasted more than the 15 year period limit provided by the AGWT advocates themselves. Anyhow, the strong warming peak observed in 2015-2016, the “hottest year on record,” gave the impression that the temperature standstill stopped in 2014. Herein, the authors show that such a temperature peak is unrelated to anthropogenic forcing: it simply emerged from the natural fast fluctuations of the climate associated to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon. By removing the ENSO signature, the authors show that the temperature trend from 2000 to 2016 clearly diverges from the general circulation model (GCM) simulations. Thus, the GCMs models used to support the AGWT [anthropogenic global warming theory] are very likely flawed. By contrast, the semi-empirical climate models proposed in 2011 and 2013 by Scafetta, which are based on a specific set of natural climatic oscillations believed to be astronomically induced plus a significantly reduced anthropogenic contribution, agree far better with the latest observations.

Kundzewicz et al., 2018 Climate models need to be improved before they can be effectively used for adaptation planning and design. Substantial reduction of the uncertainty range would require improvement of our understanding of processes implemented in models and using finer resolution of GCMs and RCMs. However, important uncertainties are unlikely to be eliminated or substantially reduced in near future (cf. Buytaert et al., 2010). Uncertainty in estimation of climate sensitivity (change of global mean temperature, corresponding to doubling atmospheric CO2 concentration) has not decreased considerably over last decades. Higher resolution of climate input for impact models requires downscaling (statistical or dynamic) of GCM outputs, adding further uncertainty. … [C]limate models do not currently simulate the water cycle at sufficiently fine resolution for attribution of catchment-scale hydrological impacts to anthropogenic climate change. It is expected that climate models and impact models will become better integrated in the future. … Calibration and validation of a hydrological model should be done before applying it for climate change impact assessment, to reduce the uncertainty of results. Yet, typically, global hydrological models are not calibrated and validated. … Model-based projections of climate change impact on water resources can largely differ. If this is the case, water managers cannot have confidence in an individual scenario or projection for the future. Then, no robust, quantitative, information can be delivered and adaptation procedures need to be developed which use identified projection ranges and uncertainty estimates. Moreover, there are important, nonclimatic, factors affecting future water resources. … As noted by Funtowicz and Ravetz (1990), in the past, science was assumed to provide “hard” results in quantitative form, in contrast to “soft” determinants of politics, that were interest-driven and value-laden. Yet, the traditional assumption of the certainty of scientific information is now recognized as unrealistic and counterproductive. Policy-makers have to make “hard” decisions, choosing between conflicting options (with commitments and stakes being the primary focus), using “soft” scientific information that is bound with considerable uncertainty. Uncertainty has been policitized in that policy-makers have their own agendas that can include the manipulation of uncertainty. Parties in a policy debate may invoke uncertainty in their arguments selectively, for their own advantage.

Hanna et al., 2018 Recent changes in summer Greenland blocking captured by none of the CMIP5 models … Recent studies note a significant increase in high-pressure blocking over the Greenland region (Greenland Blocking Index, GBI) in summer since the 1990s. … We find that the recent summer GBI increase lies well outside the range of modeled past reconstructions (Historical scenario) and future GBI projections (RCP4.5 and RCP8.5). The models consistently project a future decrease in GBI (linked to an increase in NAO), which highlights a likely key deficiency of current climate models if the recently-observed circulation changes continue to persist. Given well-established connections between atmospheric pressure over the Greenland region and air temperature and precipitation extremes downstream, e.g. over Northwest Europe, this brings into question the accuracy of simulated North Atlantic jet stream changes and resulting climatological anomalies […] as well as of future projections of GrIS mass balance produced using global and regional climate models.

Lean, 2018 Climate change detection and attribution have proven unexpectedly challenging during the 21st century. Earth’s global surface temperature increased less rapidly from 2000 to 2015 than during the last half of the 20th century, even though greenhouse gas concentrations continued to increase. A probable explanation is the mitigation of anthropogenic warming by La Niña cooling and declining solar irradiance. Physical climate models overestimated recent global warming because they did not generate the observed phase of La Niña cooling and may also have underestimated cooling by declining solar irradiance. Ongoing scientific investigations continue to seek alternative explanations to account for the divergence of simulated and observed climate change in the early 21st century, which IPCC termed a “global warming hiatus.” … Understanding and communicating the causes of climate change in the next 20 years may be equally challenging. Predictions of the modulation of projected anthropogenic warming by natural processes have limited skill. The rapid warming at the end of 2015, for example, is not a resumption of anthropogenic warming but rather an amplification of ongoing warming by El Niño. Furthermore, emerging feedbacks and tipping points precipitated by, for example, melting summer Arctic sea ice may alter Earth’s global temperature in ways that even the most sophisticated physical climate models do not yet replicate.

Hunziker et al., 2018 About 40 % of the observations are inappropriate for the calculation of monthly temperature means and precipitation sums due to data quality issues. These quality problems undetected with the standard quality control approach strongly affect climatological analyses, since they reduce the correlation coefficients of station pairs, deteriorate the performance of data homogenization methods, increase the spread of individual station trends, and significantly bias regional temperature trends. Our findings indicate that undetected data quality issues are included in important and frequently used observational datasets and hence may affect a high number of climatological studies. It is of utmost importance to apply comprehensive and adequate data quality control approaches on manned weather station records in order to avoid biased results and large uncertainties.

Roach et al., 2018 Consistent biases in Antarctic sea ice concentration simulated by climate models … The simulation of Antarctic sea ice in global climate models often does not agree with observations. [M]odels simulate too much loose, low-concentration sea ice cover throughout the year, and too little compact, high-concentration cover in the summer. [C]urrent sea ice thermodynamics contribute to the inadequate simulation of the low-concentration regime in many models.

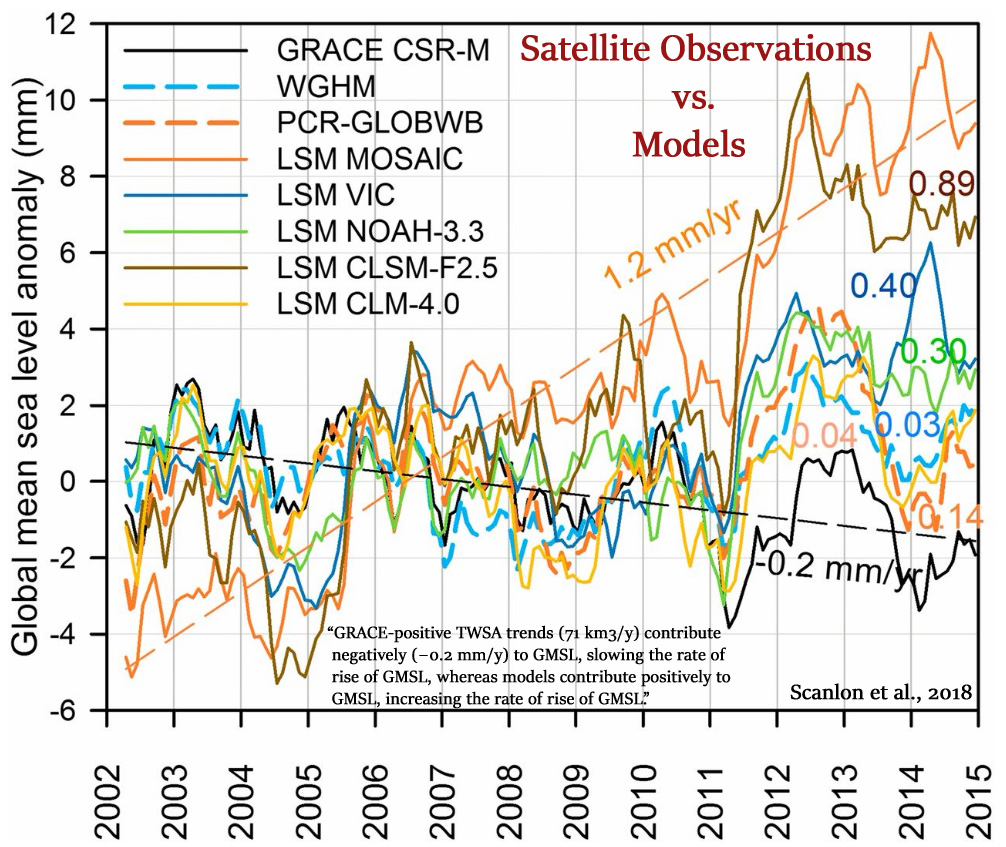

Scanlon et al., 2018 The models underestimate the large decadal (2002–2014) trends in water storage relative to GRACE satellites, both decreasing trends related to human intervention and climate and increasing trends related primarily to climate variations. The poor agreement between models and GRACE underscores the challenges remaining for global models to capture human or climate impacts on global water storage trends. … Increasing TWSA [total water storage anomalies] trends are found primarily in nonirrigated basins, mostly in humid regions, and may be related to climate variations. Models also underestimate median GRACE increasing trends (1.6–2.1 km3/y) by up to a factor of ∼8 in GHWRMs [global hydrological and water resource models] (0.3–0.6 km3/y). Underestimation of GRACE-derived TWSA increasing trends is much greater for LSMs [global land surface models], with four of the five LSMs [global land surface models] yielding opposite trends (i.e., median negative rather than positive trends) … Increasing GRACE trends are also found in surrounding basins, with most models yielding negative trends. Models greatly underestimate the increasing trends in Africa, particularly in southern Africa. .. TWSA trends from GRACE in northeast Asia are generally increasing, but many models show decreasing trends, particularly in the Yenisei. … Subtracting the modeled human intervention contribution from the total land water storage contribution from GRACE results in an estimated climate-driven contribution of −0.44 to −0.38 mm/y. Therefore, the magnitude of the estimated climate contribution to GMSL [global mean sea level] is twice that of the human contribution and opposite in sign. While many previous studies emphasize the large contribution of human intervention to GMSL [global mean sea level], it has been more than counteracted by climate-driven storage increase on land over the past decade. … GRACE-positive TWSA trends (71 km3/y) contribute negatively (−0.2 mm/y) to GMSL, slowing the rate of rise of GMSL, whereas models contribute positively to GMSL, increasing the rate of rise of GMSL.

van Oldenborgh et al., 2018 [I]t was widely assumed that the probability and severity of heat waves in India are increasing due to global warming, as they do in other parts of the world. However, we do not find positive trends in the highest maximum temperature of the year in most of India since the 1970s (except spurious trends due to missing data). Decadal variability cannot explain this, but both increased air pollution with aerosols blocking sunlight and increased irrigation leading to evaporative cooling have counteracted the effect of greenhouse gases up to now. Current climate models do not represent these processes well and hence cannot be used to attribute heat waves in this area.

Merrifield, 2018 As Deser and colleagues reported, regionally, temperature and precipitation fluctuate in an unpredictable fashion as a result of nonlinear processes in the climate system (Nat. Clim. Change2, 775–779; 2012). These fluctuations, which manifest year-to-year and decade-to-decade, obscure anthropogenic change in the near term. Though natural variability introduces irreducible uncertainty into climate projections, its influence can be accounted for. For instance, Deser et al. used a large ensemble of climate model simulations that are identical aside from initial atmospheric state to show how the influence of natural variability differs by process, region and season. Each member of the large ensemble comes from the same model and is forced with the same greenhouse gas emissions, aerosol concentrations, volcanic eruptions and solar radiation. Yet, each member still shows a different possible climate future, due to natural variability. In the case of Seattle, winter precipitation is projected to either increase or decrease by up to 20% by 2060.

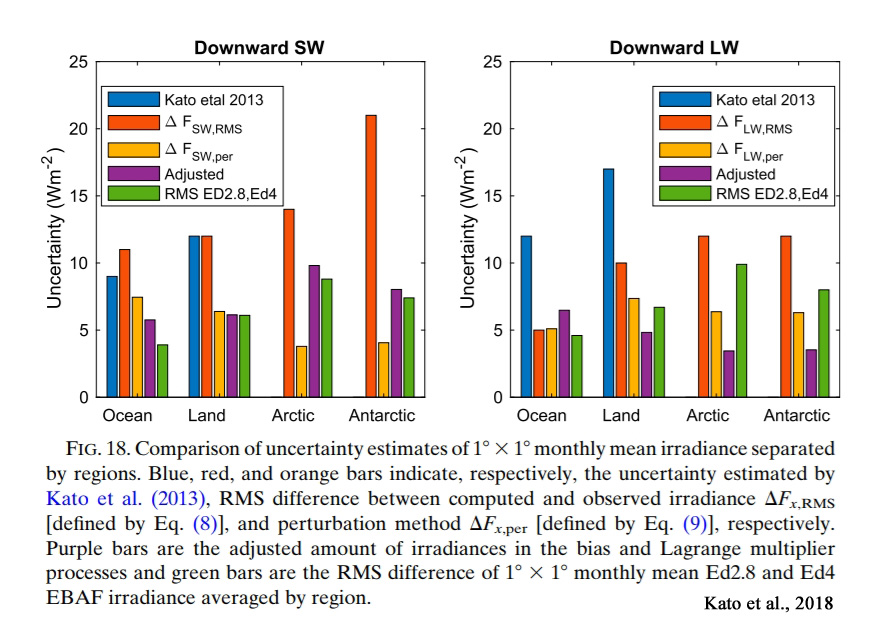

Kato et al., 2018 The uncertainty in surface irradiances over ocean, land, and polar regions at various spatial scales are estimated. The uncertainties in all-sky global annual mean upward and downward shortwave irradiance are 3 and 4 W m2, respectively, and the uncertainties in upward and downward longwave irradiance are 3 and 6 W m2, respectively. With an assumption of all errors being independent, the uncertainty in the global annual mean surface LW 1 SW net irradiance is 8 W m2. … The downward longwave irradiance emitted by the atmosphere is primarily sensitive to near-surface temperature and the amount of water vapor as well as cloud fraction and base height in the atmosphere. [CO2 is not mentioned as factor that downward longwave irradiance is “primarily sensitive” to.]

Zadra, 2018 All model evaluation efforts reveal differences when compared to observations. These differences may reflect observational uncertainty, internal variability, or errors/biases in the representation of physical processes. The following list represents errors that were noted specifically during the meeting: cloud microphysics—errors linked to mixed-phase, supercooled liquid cloud, and warm rain; precipitation over orography—spatial distribution and intensity errors; outstanding errors in the modeling of surface fluxes; errors in the representation of the diurnal cycle of surface temperature; errors in variability and trends in historical external forcings; challenges in the prediction of midlatitude synoptic regimes and blocking; model errors in the representation of teleconnections through inadequate stratosphere–troposphere coupling; and model biases in mean state, diabatic heating, SST; errors in meridional wind response and tropospheric jet stream impact simulations of teleconnections. MJO modeling—propagation, response to mean errors, and teleconnections; subtropical boundary layer clouds—still underrepresented and tending to be too bright in models; their variation with large-scale parameters remains uncertain; and their representation may have a coupled component/feedback; tropical cyclones—high-resolution forecasts tend to produce cyclones that are too intense, although moderate improvements are seen from ocean coupling; wind–pressure relationship errors are systematic

Moon et al., 2018 The persistence of drought events largely determines the severity of socioeconomic and ecological impacts, but the capability of current global climate models (GCMs) to simulate such events is subject to large uncertainties. … These findings reveal systematic errors in the representation of drought persistence in current GCMs [global climate models] and suggest directions for further model improvement.

Gray et al., 2018 Compared to ship‐based CO2 flux estimates, the float‐based fluxes find significantly stronger outgassing in the zone around Antarctica where carbon‐rich deep waters upwell to the surface ocean. Although interannual variability contributes, this difference principally stems from the lack of autumn and winter ship‐based observations in this high‐latitude region. These results suggest that our current understanding of the distribution of oceanic CO2 sources and sinks may need revision and underscore the need for sustained year‐round biogeochemical observations in the Southern Ocean.

(press release) The researchers found that a large region of the Southern Ocean near Antarctica’s sea ice released 0.36 petagrams (PgC, one billion metric tons) of carbon per year. Most of that outgassing occurred during winter months. (For comparison, global fossil-fuel burning in 2016 released 9.9 PgC.) Measurements from four other regions suggested that overall, the Southern Ocean is a weak sink that absorbs 0.08 PgC/year. Climate models tend to calculate an order of magnitude larger absorption, around 0.9 PgC/year, which is consistent with estimates from ships traversing the region primarily in summer. … The researchers conclude that an unaccounted-for carbon sink must exist elsewhere to supplement the lower-than-expected contribution of the Southern Ocean. The study suggests that current understanding of source and sink distribution may need revision and highlights the need for sustained year-round observations.

Agarwal and Wettlaufer, 2018 The fluctuation statistics of the observed sea-ice extent during the satellite era are compared with model output from CMIP5 models using a multifractal time series method. The two robust features of the observations are that on annual to biannual time scales the ice extent exhibits white noise structure, and there is a decadal scale trend associated with the decay of the ice cover. It is shown that (i) there is a large inter-model variability in the time scales extracted from the models, (ii) none of the models exhibits the decadal time scales found in the satellite observations, (iii) five of the 21 models [24%] examined exhibit the observed white noise structure, and (iv) the multi-model ensemble mean exhibits neither the observed white noise structure nor the observed decadal trend.

Simpson and Deser, 2018 Multidecadal variability in the North Atlantic jet stream in general circulation models (GCMs) is compared with that in reanalysis products of the twentieth century. … This analysis reveals a fundamental mismatch between late winter jet stream variability in observations and GCMs [general circulation models] and a potential source of long-term predictability of the late winter Atlantic atmospheric circulation.

Urban Heat Island: Raising Surface Temperatures Artificially

Han et al., 2018 In all three regions, the stations surrounded by large urban land tend to experience rapid warming, especially at minimum temperature. This dependence is particularly significant in the southeast region, which experiences the most intense urbanization. In the northwest and intermediate regions, stations surrounded by large cultivated land encounter less warming during the main growing season, especially at the maximum temperature changes. These findings suggest that the observed surface warming has been affected by urbanization and agricultural development represented by urban and cultivated land fractions around stations in with land cover changes in their proximity and should thus be considered when analyzing regional temperature changes in mainland China.

Soon et al., 2018 [T]here is considerable evidence that, in recent decades, many instrumental records in China have been affected by warming biases caused by urbanization. So, urbanization bias may have artificially inflated the apparent warmth of the recent period [1990s-present]. This would also have the effect of artificially decreasing the relative warmth of the early period [1920s-1940s]. … The main homogenization approaches currently applied in an attempt to reduce the effects of non-climatic biases have a tendency to reduce the warmth of the early period [1920s-1940s] and increase the warmth of the recent period [1990s-present]. This has led several groups to conclude that the apparent warmth of the early period is mostly due to non-climatic biases, e.g., Li et al. (2017). On the other hand, Soon et al. (2015) note that the current homogenization approaches lead to “urban blending” when applied to a highly urbanized station network. That is, the homogenization process “aliases” (deGaetano, 2006; Pielke et al., 2007a) a fraction of the urbanization bias of urban neighbours onto the records of less urbanized station. This blending problem would have a tendency to artificially increase the warmth of the recent period and decrease the warmth of the early period.

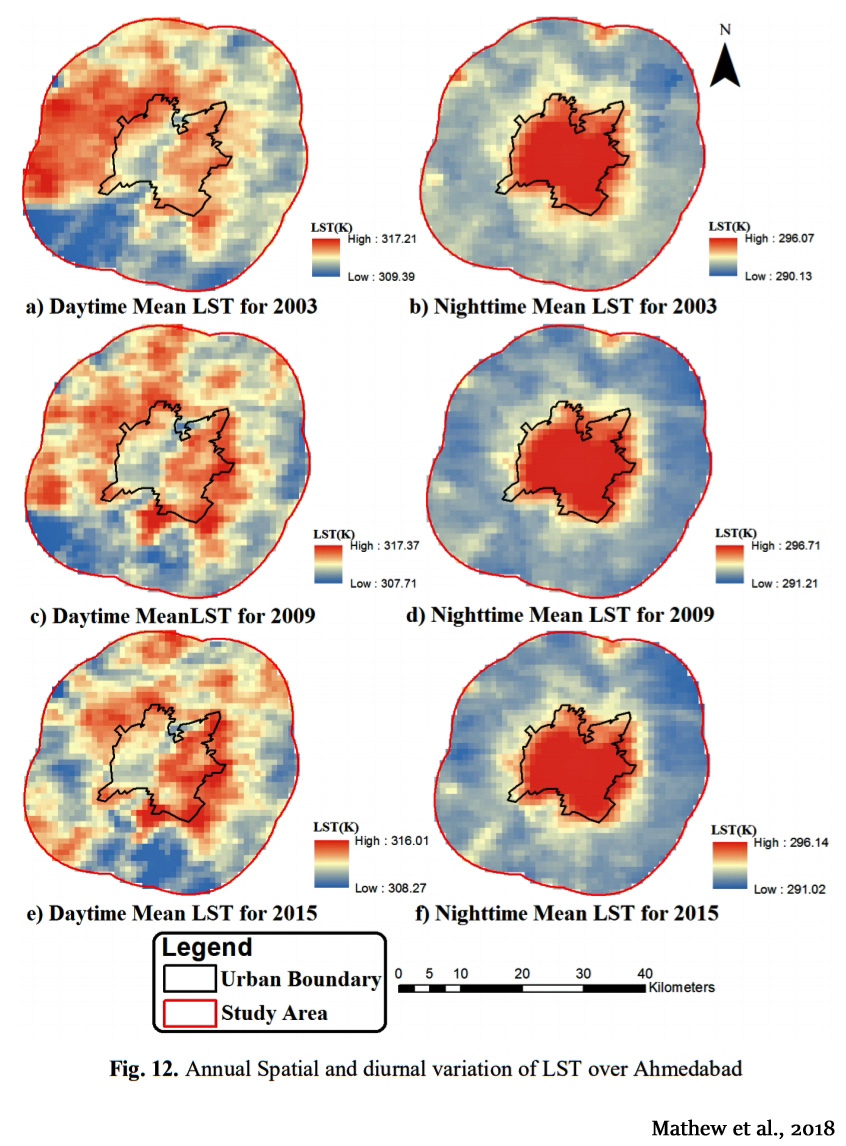

Mathew et al., 2018 Urbanization induced surface and atmospheric modifications lead to a modified thermal environment that is warmer than the neighboring rural areas, particularly at night. This phenomenon is referred as urban heat island (UHI). … Urbanization is one of the primary driving factors of land cover (LC) changes and subsequently increase of LST [land surface temperature] [Pal and Ziaul, 2016]. As an important environmental factor, LST [land surface temperature] plays a significant role in describing energy exchanges of the Earth’s land surface and atmosphere [Quattrochi et al., 1999; Weng, 2009]. LST is usually derived from thermal bands of remotely sensed data and has been considered as a primary factor for examining surface energy balance (SEB) budget [Friedl, 2002; Oke et al., 1992], assessing surface UHI (SUHI) effect [Oke, 1982; Mathew et al., 2016; Streutker, 2003; Weng and Fu, 2014; Weng et al., 2004] … Giannaros et al. [2013] have investigated that the city of Athens shows higher air temperatures than its surrounding rural areas during the night (SUHI intensity >4 K), whereas the temperature difference is less evident during early morning and mid-day hours. Observations of aerial images have confirmed that increase in albedo, such as reflective roofs, produced stronger cooling than common efforts to increase NDVI, such as green roofs, street trees and green parks [Mackey et al., 2012]. Tan and Li [2015] have observed that daytime UHI intensity is higher than the night time UHI intensity, especially for big cities. For cities with an area >100 km2 , the mean daytime UHI intensity (2.90 K) has been observed to be higher than the night time UHI intensity (2.30 K). On the basis of analysis of a large number of clusters, it has been concluded that daytime UHI intensity is more significant than night time UHI intensity for clusters with an area >2 km2 . Lokoshchenko [2014] has studied the UHI intensity of Moscow from long term temperature records and has observed a mean UHI intensity of 1.0–1.2 K at the end of the 19th century, 1.2–1.4 K during first two decades of the 20th century and 1.6–1.8 K during both the middle and at the end of the 20th century.

Ayanlade and Howard, 2018 This study aims at estimating land use change implications on land surface temperature (LST) and heat fluxes over three cities in Niger Delta region, using satellite data. The study was carried out in three major urban areas in the Niger Delta of Nigeria: Benin City, Port Harcourt and Warri. Both in situ and satellite climatological data were used in this study to estimate the variations in heat fluxes over different land use/land cover in three major urban areas around the Niger Delta region in Nigeria. The results showed a general increased in the mean LST, with average of 1.43 °C increase between year 2004 and 2015 over different urban land use. The estimated heat flux ranges from 30.55 to 102.05 W/m2in the year 2004 but increased ranges from 33.25 to 120.06 W/m2 in the year 2015. The average heat flux was nearly 30.12 W/m2 during wet season, but much higher during the dry season with average heat flux nearly 215.75 W/m2. Increase in LST [land surface temperature] appeared to be a result of changes in landuse/landcover in the cities. The results further show that different land use exhibits a different degree of LST during both wet and dry seasons, with temperature is nearly 2 °C higher in dry season compare to wet seasons. These results imply that urban expansion in the Delta has resulted in variation in boundary currents and higher temperatures in the cities area compared to its immediate rural areas. The major findings of this study are that urban climate, urban heat redistribution and other hydrosphere processes are determined by the change in land use.

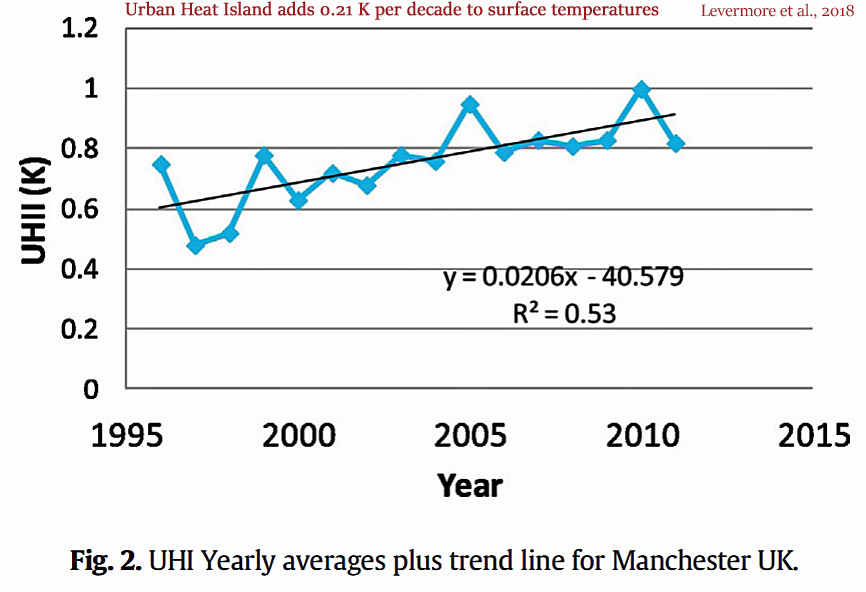

Levermore et al., 2018 This paper examines the urban heat island intensity in detail in the city of Manchester, UK [during 1996-2011]. An increasing intensity is found over time. … It was possible to assess the green space and its changes between 2000 and 2009. It can be seen that the green area has reduced by up to 11% over the whole area shown although it is only a 1.5% reduction within 200 m of the station. … Fig. 2 shows the yearly averages for UHI. There is a clear upward trend in time. The fitted trend line: UHI ¼ 0:021 YEAR−40:6 ð1Þ has a statistically significant (P b 0.1%) slope of 0.021 °C per annum [0.21°C per decade]. If this trend were to continue then over the century the UHI would be 2.42 °C. This is approximately equal to the lower predictions of climate change and is in addition to climate change. [A 1.5% to 11% reduction in green area leads to a 0.21°C per decade increase in surface temperature.]

Failing Renewable Energy, Climate Policies

DeCicco and Schlesinger, 2018 [A] major reprioritization of climate-related research, policy, and investment is urgently required, a move away from bioenergy and toward terrestrial carbon management (TCM). Researchers and policymakers must pursue actionable mitigation approaches that have the best chance of significantly reducing atmospheric CO2 concentrations in the near and medium term. … Bioenergy displaces land from prior uses, resulting in both direct and indirect land-use change. This leads to the difficult conundrum of carbon debt, i.e., the time it takes for the release of carbon stocks linked to bioenergy expansion to be paid back through future carbon uptake, which can be decades. Moreover, the realities of bioenergy production exacerbate the effects of industrial-scale agriculture on soil health, water quality, biodiversity, and other ecosystem services. … The assumption that bioenergy is inherently carbon-neutral, which is based on static forms of carbon accounting, is a major error (Haberl et al., 2012). Viewed objectively, it is quite a sweeping assumption: It asserts that a carbon flow into the atmosphere at one place and time (from bioenergy combustion) is automatically and fully offset by carbon uptake at another place and time (on ecologically productive land). Scientifically speaking, there is neither a sound basis nor a need to make this assumption. The extent to which the CO2 emitted from bioenergy use is balanced by CO2 uptake is an empirical question. … In short, a sound understanding of carbon-cycle dynamics shows that now and for the reasonably foreseeable future, the promotion of bioenergy is ill-premised for climate protection. This is particularly true if one respects the limited amount of ecologically productive land available for supplying food and fiber as well as sustaining and restoring biodiverse habitats.

Schlesinger, 2018 Recently, attention has focused on woody biomass—a return to firewood—to generate electricity. Trees remove CO2 from the atmosphere, and burning wood returns it. But recent evidence shows that the use of wood as fuel is likely to result in net CO2 emissions and may endanger forest biodiversity.

(press release) Each year, some 7 million tons of wood pellets are shipped from the United States to Europe, where biomass fuels have been declared carbon-neutral with respect to fulfilling the commitments of the Paris Climate Accord. The current goal for the European Union (EU) is to generate 20 percent of its electricity by 2020 using renewable sources, including burning woody biomass. In part to revive a languishing forest products industry, the U.S. Congress may also declare wood a carbon-neutral fuel. … With wood, there is the assumption, but no guarantee, that new trees will be planted and persist long enough to pay back the carbon debt created by combustion of the previous stands. If that carbon stock is not restored, then burning wood may actually emit more CO2 to the atmosphere than burning coal. … [T]he recent science indicates that production of wood pellets for fuel is likely to put more CO2 in the atmosphere and maintain less biodiversity on the land during the next several decades.

de Oliveira Garcia et al., 2018 Increasing global woody biomass demand may cause additional pressure on forested ecosystems, enlarging negative nutrient budget areas. … In 2014, wood and agglomerated wood products, i.e. pellets and briquettes, provided almost half (45%) of EU-28’s total inland energy production by renewables. Current European renewable energy policy will boost woody biomass demand and, considering 2015 as baseline, the global woody biomass demand is expected to be 23 × 106 t a−1 in 2024 representing a 70% increase. For 2050, global woody biomass use for energy is expected to increase by 1.6 × 1010 t a−1 (obtained from 2.3 × 1010 m3 a−1 by assuming 0.7 t m−3 as average woody biomass bulk density) representing a potential energy production ranging from 2.7–3 × 1020 J a−1 (for a 1.7–1.9 × 1010 J t−1 biomass’ energy output). By the late 21st century, the biomass energy production is expected to be 2.4–8.5 × 1020 J a−1 13, which is approximately two orders of magnitude higher than the 2016 biomass energy production of 1.8 × 1018 J a−1 14.

Krause et al., 2018 Results suggest large uncertainty in simulated future land demand and carbon uptake rates, depending on the assumptions related to land use and land management in the models. Total cumulative carbon uptake in the DGVMs [dynamic global vegetation models] is highly variable across mitigation scenarios, ranging between 19 and 130 GtC by year 2099. Only one out of the 16 combinations of mitigation scenarios and DGVMs achieves an equivalent or higher carbon uptake than achieved in the land‐use models. The large differences in carbon uptake between the DGVMs and their discrepancy against the carbon uptake in IMAGE and MAgPIE are mainly due to different model assumptions regarding bioenergy crop yields and due to the simulation of soil carbon response to land‐use change.

Scheidel et al., 2018 Efforts to combat global climate change through forestry plantations designed to sequester carbon and promote sustainable development are on the rise. This paper analyses the trajectory of Cambodia´s first large-scale reforestation project awarded within the context of climate change mitigation. The 34,007 ha concession was formally conceived to promote sustainable resource use, livelihood improvements and emission reduction. On the ground, however, vast tracks of diverse forest landscapes are being cleared and converted to acacia monocultures, existing timber stocks are logged for market sale, and customary land users dispossessed from land and forest resources. While the project adds to an ongoing land grab crisis in Cambodia, we argue that the explicit environmental ends of the forestry concession enabled a ‘green grab’ that not only exceeds the scale of land grabs caused by conventional economic land concessions, but surprisingly also exacerbates forest logging and biodiversity loss in the area. This case demonstrates the extent to which current climate change discourses, forestry agendas and their underlying assumptions require critical revision in global policy discussions to forestall the growing problem of green grabbing in land use.

Vigil, 2018 The complex impacts of climate change on human mobility have gained increased attention, but an invisible and growing number of people are also being displaced – paradoxically – by the very measures taken in the name of addressing it. Although mitigation and adaption interventions are crucial in order to decrease the likelihood of forced displacement, response measures such as agro-fuel production and carbon forest projects have been amongst the main drivers of the global land rush which is unprecedented in scale since the colonial era. These green grabs, or ‘appropriations of natural resources for environmental ends’, are serving to cleanse the image of polluters, with devastating social and environmental consequences. The logic behind market-driven initiatives is that we should ‘sell nature in order to save it’ and that unsustainable practices in one place can be repaired by sustainable ones in another. With regard to displacement, they assume that their negative effects can be balanced by the gains in environmental protection. However, and although the presence of certain entities (mostly corporations and extractive industries) is indeed negative for the environment, it is local populations and indigenous peoples – who are the best positioned to protect natural resources – that are being evicted. Although land and green grabs are occurring worldwide, it is in countries where the protection of human rights is low, or inexistent, that they have reached the most alarming peaks. Due to a combination of international and domestic drivers, Africa has been by far the most targeted continent. Tropical forests are typically under the formal control of the government and it is relatively simple to expropriate them from inhabitants in the name of climate mitigation.

Schäfer et al., 2018 Multiple types of fluctuations impact the collective dynamics of power grids and thus challenge their robust operation.

(press release) More renewables mean less stable grids, researchers find … [I]ntegrating growing numbers of renewable power installations and microgrids onto the grid can result in larger-than-expected fluctuations in grid frequency.

Jewell et al., 2018 Hopes are high that removing fossil fuel subsidies could help to mitigate climate change by discouraging inefficient energy consumption and levelling the playing field for renewable energy. Here we show that removing fossil fuel subsidies would have an unexpectedly small impact on global energy demand and carbon dioxide emissions and would not increase renewable energy use by 2030. Removing subsidies in most regions would deliver smaller emission reductions than the Paris Agreement (2015) climate pledges and in some regions global subsidy removal may actually lead to an increase in emissions, owing to either coal replacing subsidized oil and natural gas or natural-gas use shifting from subsidizing, energy-exporting regions to non-subsidizing, importing regions.

Cradden and McDermott, 2018 Prolonged cold spells were experienced in Ireland in the winters of 2009–10 and 2010–11, and electricity demand was relatively high at these times, whilst wind generation capacity factors were low. Such situations can cause difficulties for an electricity system with a high dependence on wind energy.

Blazquez et al., 2018 However, promoting renewables –in liberalized power markets– creates a paradox in that successful penetration of renewables could fall victim to its own success. With the current market architecture, future deployment of renewable energy will necessarily be more costly and less scalable. Moreover, transition towards a full 100% renewable electricity sector is unattainable. Paradoxically, in order for renewable technologies to continue growing their market share, they need to co-exist with fossil fuel technologies. … The paradox is that the same market design and renewables policies that led to current success become increasingly less successful in the future as the share of renewables in the energy mix grows. … Full decarbonization of a power sector that relies on renewable technologies alone, given the current design of these markets, is not possible as conventional technologies provide important price signals. Markets would collapse if the last unit of fossil fuel technologies was phased out. In the extreme (theoretical) case of 100 percent renewables, prices would be at the renewables marginal cost, equal to zero or even negative for long periods. These prices would not be capturing the system’s costs nor would they be useful to signal operation and investment decisions. The result would be a purely administered subsidy, i.e., a non-market outcome. This is already occurring in Germany as Praktiknjo and Erdmann [31] point out and is clearly an unstable outcome. Thus, non-dispatchable technologies need to coexist with fossil fuel technologies. This outcome makes it impossible for renewables policy to reach success, defined as achieving a specified level of deployment at the lowest possible cost. With volatile, low and even negative electricity prices, investors would be discouraged from entering the market and they would require more incentives to continue to operate.

Marques et al., 2018 The installed capacity of wind power preserves fossil fuel dependency. … Electricity consumption intensity and its peaks have been satisfied by burning fossil fuels. … [A]s RES [renewable energy sources] increases, the expected decreasing tendency in the installed capacity of electricity generation from fossil fuels, has not been found. Despite the high share of RES in the electricity mix, RES, namely wind power and solar PV, are characterised by intermittent electricity generation. … The inability of RES-I [intermittent renewable energy sources like wind and solar] to satisfy high fluctuations in electricity consumption on its own constitutes one of the main obstacles to the deployment of renewables. This incapacity is due to both the intermittency of natural resource availability, and the difficulty or even impossibility of storing electricity on a large scale, to defer generation. As a consequence, RES [renewable energy sources] might not fully replace fossil sources … The literature proves the existence of a unidirectional causality running from RES [renewable energy sources] to NRES [non-renewable energy sources] (Almulali et al., 2014; Dogan, 2015; Salim et al., 2014). This unidirectional causality proves the need for countries to maintain or increase their installed capacity of fossil fuel generation, because of the characteristics of RES production. … In fact, the characteristics of electricity consumption reinforce the need to burn fossil fuels to satisfy the demand for electricity. Specifically, the ECA results confirm the substitution effect between the installed capacity of solar PV and fossil fuels. In contrast, installed wind power capacity has required all fossil fuels and hydropower to back up its intermittency in the long-run equilibrium. The EGA outcomes show that hydropower has been substituting electricity generation through NRES [non-renewable energy sources], but that other RES have needed the flexibility of natural gas plants, to back them up. … [D]ue to the intermittency phenomenon, the growth of installed capacity of RES-I [intermittent renewable energy sources – wind power] could maintain or increase electricity generation from fossil fuels. … In short, the results indicate that the EU’s domestic electricity production systems have preserved fossil fuel generation, and include several economic inefficiencies and inefficiencies in resource allocation. … [A]n increase of 1% in the installed capacity of wind power provokes an increase of 0.26%, and 0.22% in electricity generation from oil and natural gas, respectively in the long-run.

Sterman et al., 2018 [G]overnments around the world are promoting biomass to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The European Union declared biofuelsto be carbon-neutral to help meet its goal of 20% renewable energy by 2020, triggering a surge in use of wood for heat and electricity (European Commission 2003, Leturcq 2014, Stupak et al 2007). … But do biofuels actually reduce GHG emissions? … [A]lthough wood has approximately the same carbon intensity as coal (0.027 vs. 0.025 tC GJ−1 of primary energy […]), combustion efficiency of wood and wood pellets is lower (Netherlands Enterprise Agency; IEA 2016). Estimates also suggest higher processing losses in the wood supply chain (Roder et al 2015). Consequently, wood-fired power plants generate more CO2 per kWh than coal. Burning wood instead of coal therefore creates a carbon debt—an immediate increase in atmospheric CO2 compared to fossil energy—that can be repaid over time only as—and if— NPP [net primary production] rises above the flux of carbon from biomass and soils to the atmosphere on the harvested lands. … Growth in wood supply causes steady growth in atmospheric CO2 because more CO2 is added to the atmosphere every year in initial carbon debt than is paid back by regrowth, worsening global warming and climate change. The qualitative result that growth in bioenergy raises atmospheric CO2 does not depend on the parameters: as long as bioenergy generates an initial carbon debt, increasing harvests mean more is ‘borrowed’ every year than is paid back. More precisely, atmospheric CO2 rises as long as NPP [net primary production] remains below the initial carbon debt incurred each year plus the fluxes of carbon from biomass and soils to the atmosphere. … [C]ontrary to the policies of the EU and other nations, biomass used to displace fossil fuels injects CO2 into the atmosphere at the point of combustion and during harvest, processing and transport. Reductions in atmospheric CO2 come only later, and only if the harvested land is allowed to regrow.

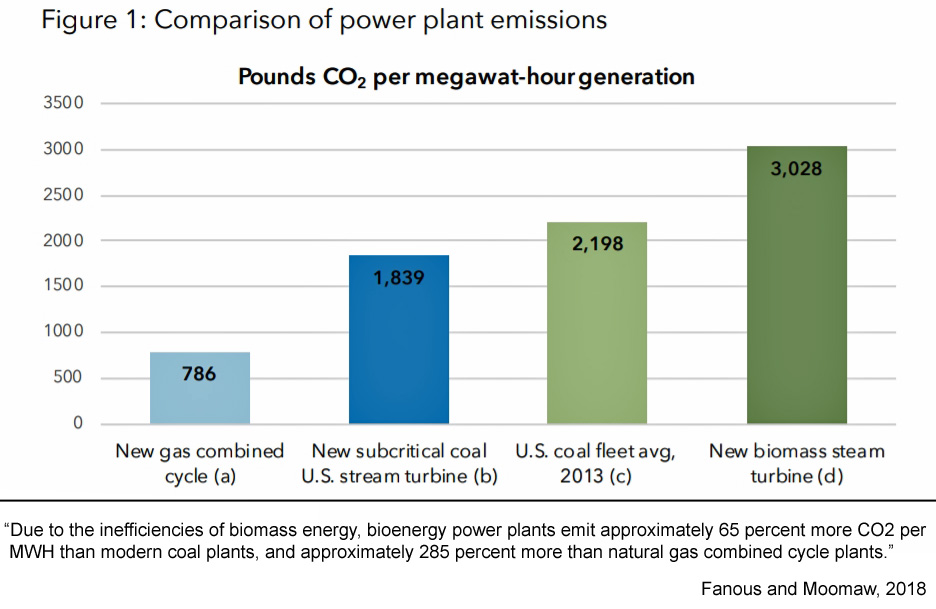

Fanous and Moomaw, 2018 These nations fail to recognize the intensity of CO2 emissions linked to the burning of biomass. The chemical energy stored in wood is converted into heat or electricity by way of combustion and is sometimes used for combined heat and power cogeneration. At the point of combustion, biomass emits more carbon per unit of heat than most fossil fuels. Due to the inefficiencies of biomass energy, bioenergy power plants emit approximately 65 percent more CO2, per MWH than modern coal plants, and approximately 285 percent more than natural gas combined cycle plants. Furthermore, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that combustion of biomass generates gross greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions roughly equivalent to the combustion of fossil fuels. In the case of forest timber turned into wood pellets for bioenergy use, the IPCC further indicates that the process produces higher CO2 emissions than fossil fuels for decades to centuries.

Lee and Jung, 2018 The results of the autoregressive distributed lag bounds test show that renewable energy consumption has a negative effect on economic growth, and the results of a vector error correction mechanism causality tests indicate a unidirectional relationship from economic growth to renewable energy consumption. The empirical results imply that economic growth is a direct driver expanding renewable energy use. In terms of policy implications, it is best for policy makers to focus on overall economic growth rather than expanding renewable energy to drive economic growth. … [O]ur result suggests that renewable energy policy should be implemented when the real GDP is enough large to overcome the negative impact from renewable energy, because the causality from economic growth to renewable energy consumption in the long run as one of our result is caused by both low productivity of renewable energy production and expansion of government-led renewable energy.

Moomaw, 2018 The European Union aims to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy, but ignores the fact that burning wood from forests releases carbon dioxide. Instead, bioenergy emissions are officially counted as zero or carbon neutral. … The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change summarized the emissions of bioenergy use as follows: “The combustion of biomass generates gross GHG emissions roughly equivalent to the combustion of fossil fuels.” When wood is burned to produce electricity, it releases an estimated 80% more carbon dioxide per unit of electricity than coal. This work by Dr. Sterman of MIT and his colleagues provides the first quantitative comparison of the total carbon emissions from forest bioenergy throughout the full carbon cycle, and compares them to coal, and renewables for a variety of bioenergy scenarios. … Burning wood to make electricity is also far more costly than deploying solar or wind technologies, and is only made economic by the European governments billions of dollars in annual subsidies. … A 2016 study found that 45% of EU renewable energy was from burning wood, and by 2020 the amount would equal the total EU harvest. According to an analysis of the new EU directive, conducted at Princeton University, “To supply even one third of the additional renewable energy likely required by 2030, Europe would need to burn an amount of wood greater than its total harvest today.”

Miller and Keith, 2018 We find that generating today’s US electricity demand (0.5 TW e) with wind power would warm Continental US surface temperatures by 0.24°C. Warming arises, in part, from turbines redistributing heat by mixing the boundary layer. Modeled diurnal and seasonal temperature differences are roughly consistent with recent observations of warming at wind farms, reflecting a coherent mechanistic understanding for how wind turbines alter climate. The warming effect is: small compared with projections of 21st century warming, approximately equivalent to the reduced warming achieved by decarbonizing global electricity generation, and large compared with the reduced warming achieved by decarbonizing US electricity with wind. For the same generation rate, the climatic impacts from solar photovoltaic systems are about ten times smaller than wind systems. Wind’s overall environmental impacts are surely less than fossil energy. Yet, as the energy system is decarbonized, decisions between wind and solar should be informed by estimates of their climate impacts.

(press release) A new study by a pair of Harvard researchers finds that a high amount of wind power could mean more climate warming, at least regionally and in the immediate decades ahead. The paper raises serious questions about just how much the United States or other nations should look to wind power to clean up electricity systems. … The study, published in the journal Joule, found that if wind power supplied all US electricity demands, it would warm the surface of the continental United States by 0.24˚C. That could significantly exceed the reduction in US warming achieved by decarbonizing the nation’s electricity sector this century, which would be around 0.1˚C.

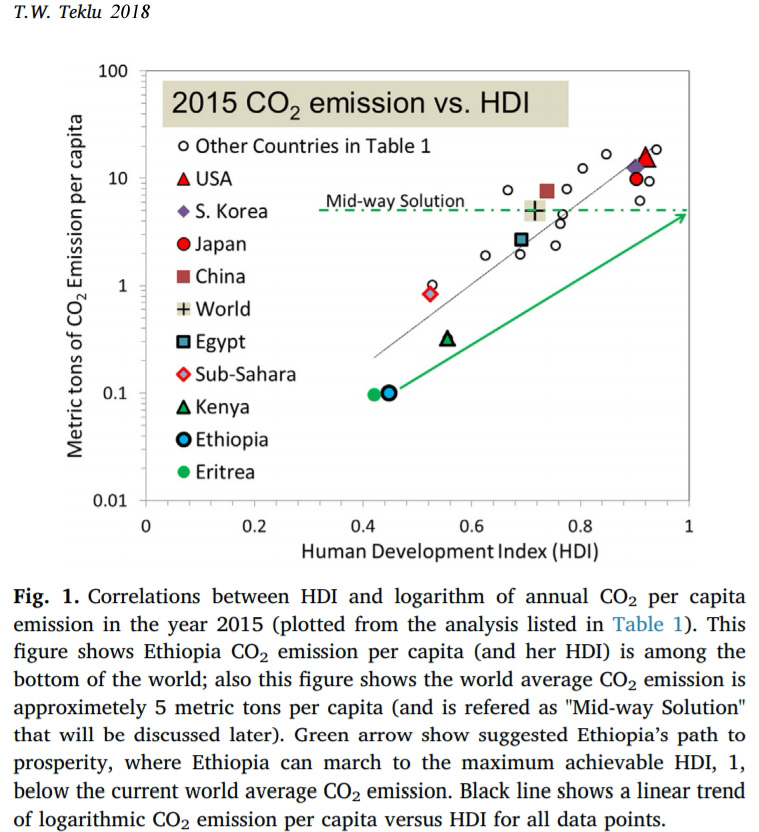

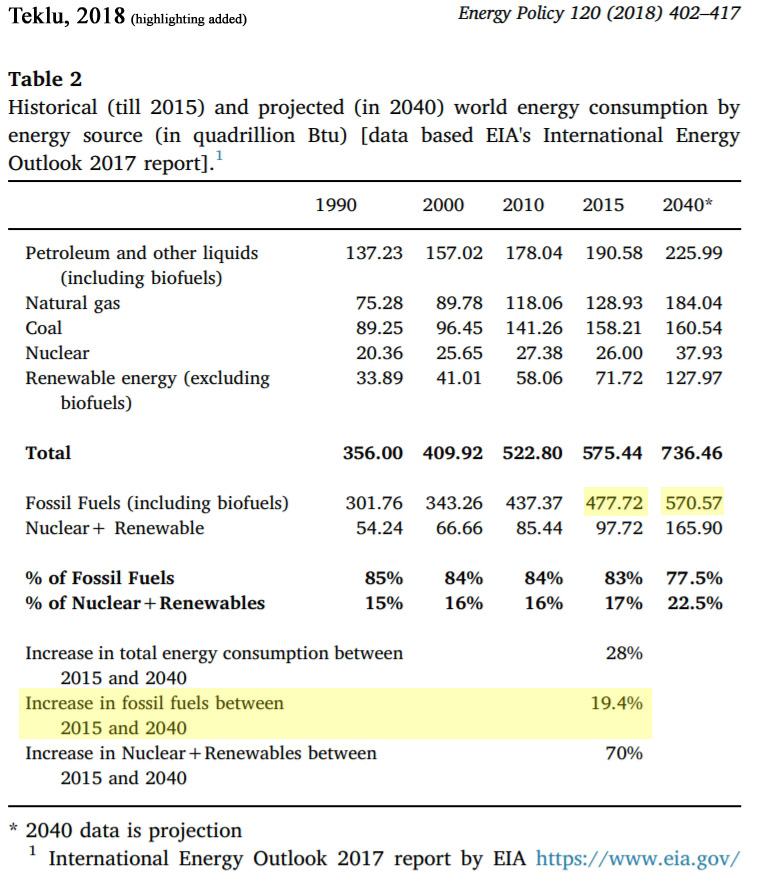

Teklu, 2018 In this study, it is argued, Ethiopia should in principle agree with the World in international climate change agreements (such as the Paris climate accord), purely to avoid any political and economic sanctions from “Earth friendly” nations and institutions; however, [Ethopia] should avoid becoming carbon neutral at the expense of adding costs and slowing her industrial development prospects. In fact, since CO2 emission (energy consumption) is directly correlated to economic prosperity and industrialization (see Table 1 and Figure 1), Ethiopia should plan to increase her CO2 emission per capita as much as possible. Ethiopia should understand that climate agreements such as the Paris accord are designed and destined to fail. Hence, Ethiopia should avoid carbon-tax, different form of financial aid, poverty-trap; instead she should plan on how to live with the inevitable global atmospheric CO2 concentration increase. The same is true for majority of least developed countries (LDCs). Global climate change [as an] issue could be a neo-colonialism and neo-cold-war instrument designed by neo-liberal institutions; hence, if Ethiopia is willing to confront any political and economic burden from “Earth friendly” nations and institutions, Ethiopia should lead other Africans’ towards the mid-way solution; and if “Earth friendly” countries does not agree with such just and simple solution; then, Ethiopia should lead Africa, in following USA, and exit from the Paris climate accord. In doing so, Ethiopia may repeat the leadership role she played during African decolonization struggle.

Miller and Keith, 2018 Power density is the rate of energy generation per unit of land surface area occupied by an energy system. The power density of low-carbon energy sources will play an important role in mediating the environmental consequences of energy system decarbonization as the world transitions away from high power-density fossil fuels. All else equal, lower power densities mean larger land and environmental footprints. The power density of solar and wind power remain surprisingly uncertain: estimates of realizable generation rates per unit area for wind and solar power span 0.3–47 We m−2 and 10–120 We m−2 respectively. We refine this range using US data from 1990–2016. We estimate wind power density from primary data, and solar power density from primary plant-level data and prior datasets on capacity density. The mean power density of 411 onshore wind power plants in 2016 was 0.50 We m−2. Wind plants with the largest areas have the lowest power densities. Wind power capacity factors are increasing, but that increase is associated with a decrease in capacity densities, so power densities are stable or declining. If wind power expands away from the best locations and the areas of wind power plants keep increasing, it seems likely that wind’s power density will decrease as total wind generation increases. The mean 2016 power density of 1150 solar power plants was 5.4 We m−2. Solar capacity factors and (likely) power densities are increasing with time driven, in part, by improved panel efficiencies. Wind power has a 10-fold lower power density than solar, but wind power installations directly occupy much less of the land within their boundaries. The environmental and social consequences of these divergent land occupancy patterns need further study. … Power densities clearly carry implications for land use. Meeting present-day US electricity consumption, for example, would require 12% of the Continental US land area [about 350,000 square miles or 912,000 square kilometers] for wind at 0.5 We m−2, or 1% for solar at 5.4 We m−2.

Wind Power Harming The Environment, Biosphere

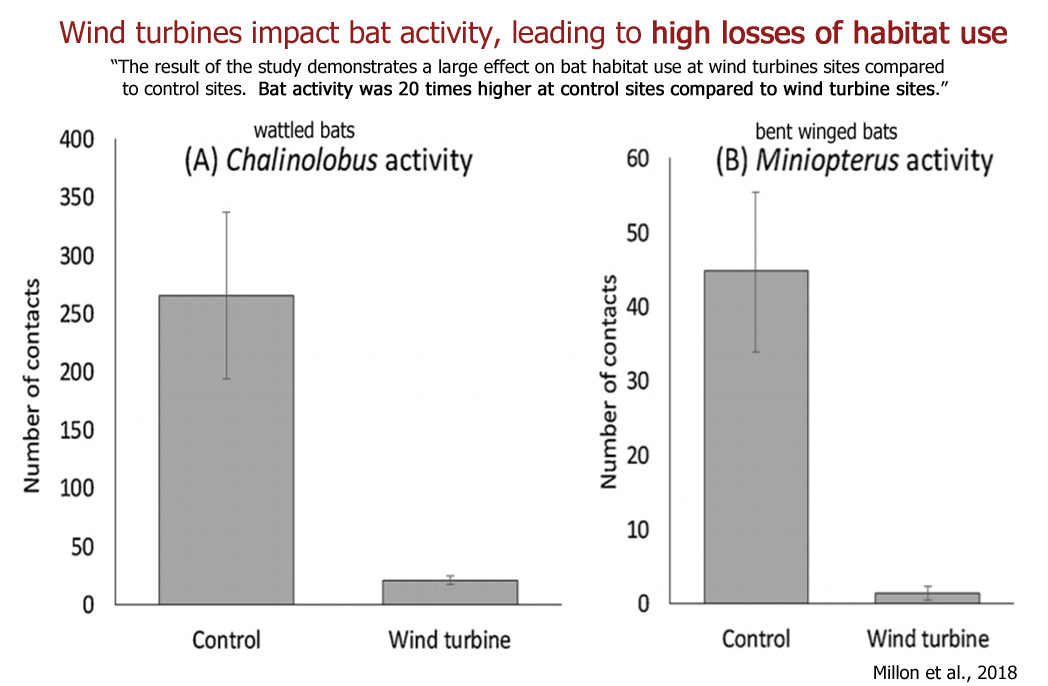

Millon et al., 2018 (full paper) Wind turbines impact bat activity, leading to high losses of habitat use … Island bats represent 60% of bat species worldwide and the highest proportion of terrestrial mammals on isolated islands, including numerous endemic and threatened species (Fleming and Racey, 2009). … We present one of the first studies to quantify the indirect impact of wind farms on insectivorous bats in tropical hotspots of biodiversity. Bat activity [New Caledonia, Pacific Islands, which hosts nine species of bat] was compared between wind farm sites and control sites, via ultrasound recordings at stationary points [A bat pass is defined as a single or several echolocation calls during a five second interval.] The activity of bent winged bats (Miniopterus sp.) and wattled bats (Chalinolobus sp.) were both significantly lower at wind turbine sites. The result of the study demonstrates a large effect on bat habitat use at wind turbines sites compared to control sites. Bat activity was 20 times higher at control sites compared to wind turbine sites, which suggests that habitat loss is an important impact to consider in wind farm planning. … Here, we provide evidence showing that two genera of insectivorous bat species are also threatened by wind farms. … To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies quantifying the indirect negative impact of wind turbines on bat activity in the tropics. … The lower attractiveness of the foraging habitat under wind turbines, both in a tropical and in a temperate climate, indicates that the indirect impact of wind turbine is a worldwide phenomenon.

Lopucki et al., 2018 Living in habitats affected by wind turbines may result in an increase in corticosterone levels in ground dwelling animals … Environmental changes and disturbance factors caused by wind turbines may act as potential stressors for natural populations of both flying and ground dwelling animal species. The physiological stress response results in release of glucocorticoid hormones. … The common vole showed a distinct physiological response − the individuals living near the wind turbines had a higher level of corticosterone [physiological stress affecting regulation of energy, immune reactions]. … This is the first study suggesting impact of wind farms on physiological stress reactions in wild rodent populations. Such knowledge may be helpful in making environmental decisions when planning the development of wind energy and may contribute to optimization of conservation actions for wildlife.

Ferrão da Costa et al., 2018 According to a review by Lovich and Ennen (2013), the construction and operation of wind farms have both potential and known impacts on terrestrial vertebrates, such as: (i) increase in direct mortality due to traffic collisions; (ii) destruction and modification of the habitat, including road development, habitat fragmentation and barriers to gene flow; (iii) noise effects, visual impacts, vibration and shadow flicker effects from turbines; (iv) electromagnetic field generation; (v) macro and microclimate change; (vi) predator attraction; and (vii) increase in fire risks. … Helldin et al. (2012) also highlighted that the development of road networks associated with wind farms could promote increased access for traffic related to recreation, forestry, agriculture and hunting. The consequence, particularly on remote places, is the increase in human presence, affecting large mammals via significant disturbance, habitat loss and habitat fragmentation. These negative effects are expected to be particularly relevant for species that are more sensitive to human presence and activities, such as large carnivores. Large carnivores, such as the wolf, bear, lynx or wolverine, tend to avoid areas that are regularly used by humans and—especially for breeding—show a preference for rugged and undisturbed areas (Theuerkauf et al. 2003; George and Crooks 2006; May et al. 2006; Elfstrom et al. 2008; Sazatornil et al. 2016), which are often chosen for wind power development (Passoni et al. 2017). … Results have shown that the main impact of wind farms on wolves is the induced reduction on breeding site fidelity and reproductive rates. These effects, particularly when breeding sites shift to more unsuitable areas, may imply decreasing survival and pack viability in the short term.

Watson et al., 2018 The global potential for wind power generation is vast, and the number of installations is increasing rapidly. We review case studies from around the world of the effects on raptors of wind-energy development. Collision mortality, displacement, and habitat loss have the potential to cause population-level effects, especially for species that are rare or endangered.

Aschwanden et al., 2018 The extrapolated number of collisions was 20.7 birds/wind turbine (CI-95%: 14.3–29.6) for 8.5 months. Nocturnally migrating passerines, especially kinglets (Regulus sp.), represented 55% of the fatalities. 2.1% of the birds theoretically exposed to a collision (measured by radar at the height of the wind turbines) were effectively colliding.

Naylor, 2018 While wind energy provides a viable solution for emission reductions, it comes at an environmental cost, particularly for birds. As wind energy grows in popularity, its environmental impacts are becoming more apparent. Recent studies indicate that wind power has negative effects on proximate wildlife. These impacts can be direct—collision fatalities—and indirect—habitat loss (Fargione et al. 2012; Glen et al. 2013). Negative impacts associated with operational wind farms include collision mortalities from towers or transmission lines and barotrauma for bats. Habitat loss and fragmentation, as well as avoidance behavior, are also consequences resulting from wind farm construction and related infrastructure. The potential harm towards protected and migratory bird species are an urgent concern, especially for wind farms located along migratory flyways. In terms of mortality, wind turbines kill an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 birds, annually (Smallwood 2013). The high speed at which the fan wings move and the concentration of turbines create a gauntlet of hazards for birds to fly through. … [T]he height of most wind turbines aligns with the altitude many bird species fly at (Bowden 2015). Birds of prey— raptors—are of particular concern because of their slow reproductive cycles and long lifespans relative to other bird species (Kuvlesky 2007).

Lange et al., 2018 Results from our surface water extractions and aerial surveys suggest that the wind farm has negatively affected redheads through altered hydrology and disturbance displacement. Our surface water extraction analysis provides compelling evidence that the local hydrology has been greatly affected by the construction of the wind farm. … Our results suggest the occurrence of direct habitat loss and disturbance displacement of redheads from the wind farm along the lower Texas coast. Although our study was directed solely toward redheads, it is likely that this wind farm has affected other species that use these wetlands or migrate along the lower Texas coast (Contreras et al. 2017). Studies in Europe investigating the effects on waterfowl by wind turbines have reported similar results, showing that turbines have likely compromised foraging opportunities for waterfowl through disturbance displacement (Larsen and Madsen 2000).

Barry et al., 2018 The findings indicate that residential proximity to wind turbines is correlated with annoyance and health-related quality of life measures. These associations differ in some respects from associations with noise measurements. Results can be used to support discussions between communities and wind-turbine developers regarding potential health effects of wind turbines.

Chiebáo, 2018 I studied the large-scale movements of white-tailed eagles during the dispersal period, assessing their space use in relation to the distribution of existing and proposed wind farms across Finland. I found that a breeding pair holding a territory closer to an installation has a lower probability to breed successfully when compared to a pair from a territory lying farther away. Such lower probability may in part reflect a harmful interaction between the eagles and wind turbines in the form of collision mortality, to which the adults appear to be particularly vulnerable during the breeding season. Regarding the post-fledging period, I found that the probability of a young eagle approaching a wind turbine decreases sharply as the turbine is installed at increasing distances from the nest.

Shakespear, 2018 A trend was found, whereby developing countries tend to suffer the most socio-environmental disruption from material extraction for solar-panels and wind-turbines while exhibiting lower implementation of these technologies, and developed countries show opposite effects. This indicates that EUE [ecologically unequal exchange] effects constitute global solar-panel and wind-turbine systems, and that developed countries displace socio-environmental disruption from energy innovation onto developing countries. … [I]mplementation of solarpanels and wind-turbines tended to be the most prevalent within countries that suffer the least environmental and socio-economic consequences from the extraction of materials for these technologies. This effectively means that efforts to increase sustainability in relatively powerful countries via renewable energy implementation exacerbates unsustainable practices in the relatively less powerful countries that extract the minerals for these technologies.

Barré et al., 2018 Wind energy is rapidly growing as a renewable source of energy but is not neutral for wildlife, especially bats. Whereas most studies have focused on bat mortality through collision, very few have quantified the loss of habitat use resulting from the potential negative impact of wind turbines … We quantified the impact of wind turbines at different distances on the activity of 11 bat taxa and 2 guilds. … We found a significant negative effect of proximity to turbines on activity for 3 species (Barbastella barbastellus, Nyctalus leisleiri, Pipistrellus pipistrellus), 2 species-groups (Myotis spp., Plecotus spp.) and 2 guilds (fast-flying and gleaner). … The current situation is particularly worrying, with 89% of 909 turbines established in a region that does not comply with recommendations, which themselves are far from sufficient to limit the loss of habitat use. … [T]here is an urgent need to assess the potential decrease in bat activity close to wind turbines in order to quantify the changes of habitat use and the distance of impact. This possible underestimated impact of wind turbines could constitute an important concern, affecting population dynamics with a loss of habitat availability (Rodrigues et al., 2015). … [F]or most species, the negative effect of wind turbines on activity extends at least 1000 m from a wind turbine. The lost activity was therefore likely underestimated and occurred at > 1000 m. Thus, the percentage of lost activity was high, even at long-distances: for instance, at 500 m from the nearest turbine, we detected activity losses of 57% and 77% for P. pipistrellus and the gleaner species guild, respectively (Fig. 3). … Among the 909 wind turbines in northwest France, which contained the studied farms, 89% were established at < 200 m from any type of wooded edges (forest or hedgerows).

Thaker et al., 2018 [W]e find that wind farms reduce the abundance and activity of predatory birds (for example, Buteo, Butastur and Elanus species), which consequently increases the density of lizards, Sarada superba. … [W]e find that wind farms have emerging impacts that are greatly underestimated. There is thus a strong need for an ecosystem-wide view when aligning green-energy goals with environment protection.

(press release) Wind farms act as a top “predator” in some ecosystems, harming birds at the top of the food chain and triggering a knock-on effect overlooked by green energy advocates, scientists said Monday. … Close to 17 million hectares—an area roughly the size of Tunisia—is currently used for generating wind energy worldwide, and researchers warned that developers had “greatly underestimated” the impact the technology has on wildlife. In new research, an international team of scientists studied the effects of wind turbine use in the Western Ghats, a UNESCO-listed range of mountains and forest spanning India’s west coast region and a global “hotspot” of biodiversity. They found that predatory raptor birds were four times rarer in areas of plateau where wind turbines were present, a disruption that cascaded down the food chain and radically altered the density and behaviour of the birds’ prey. … Wind farms are known to be harmful to birds, disrupting their migration patterns and causing above average death rates. Thaker said her research, published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, showed that wind farms replicated the role of the top predator in the food chain by keeping the raptors at bay. “They trigger changes to the balance of animals in an ecosystem as if they were top predators,” she said.

Ishitake, 2018 We investigated whether long-term exposure to low-frequency noise generated by wind power facilities is a risk factor for sleep disorders. We performed an epidemiological study of the living environment and health effects of such noise by surveying 9,000 residents (≥20 years of age) living in areas with operational wind power facilities. Sleep disorders were assessed using the Athens Insomnia Scale. To assess environmental noise in residential areas near wind turbines, infrasound and low-frequency sound exposure levels were measured at 50 community centers of a town. The prevalence of sleep disorders was significantly higher among residents who reported subjectively hearing noise (by approximately twofold) than among those who did not. Moreover, the reported prevalence of sleep disorders was significantly higher (by approximately twofold) among residents living at a distance of ≤1,500 m from the nearest wind turbine than among residents living at a distance of ≥2,000 m, suggesting a dose-response relationship. The attitudes of residents towards wind power facilities strongly affected their responses regarding sleep disorder prevalence. It is highly likely that audible noise generated by wind power facilities is a risk factor for sleep disorders. Obtaining a satisfactory consensus from local residents before installing wind power facilities is important as for more amenable their attitudes towards such facilities.

Jensen et al., 2018 We present the results of a large-scale analysis on how on-shore and off-shore wind turbines affect the property prices of nearby single family residential and vacation homes in Denmark. We find that on-shore wind turbines negatively affect the price of surrounding properties to a distance of three kilometers. The negative impact increases with the number of wind turbines at a declining marginal rate but declines with distance. In the case of off-shore wind turbine farms, we do not find a significant effect of having an off-shore wind farm in view from a property itself or from the nearest beach, likely because the closest off-shore turbine is 9 km from the closest traded home. … The results suggest that ceteris paribus, wind turbine farms should be built quite far away from residential areas with turbines gathered in larger wind farms rather than installed as single turbines.