History of the AGW narrative of the IPCC

Kyoji Kimoto, kyoji@mirane.co.jp

Independent climate researcher

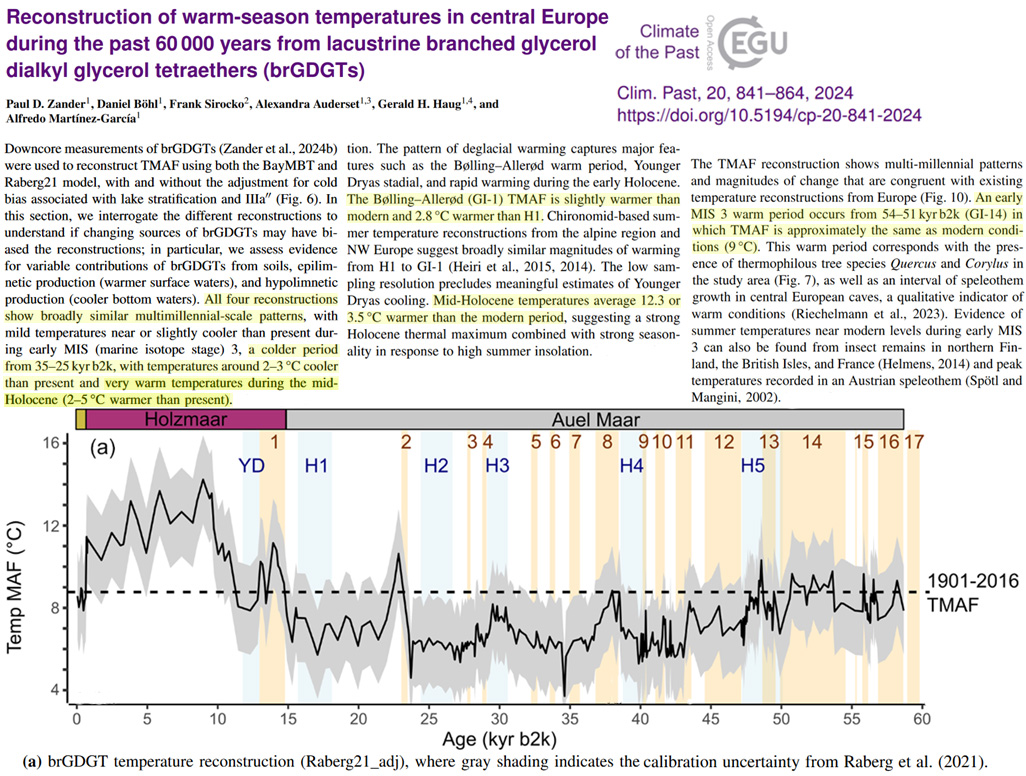

Manabe’s model studies debunked by Newell (1979)

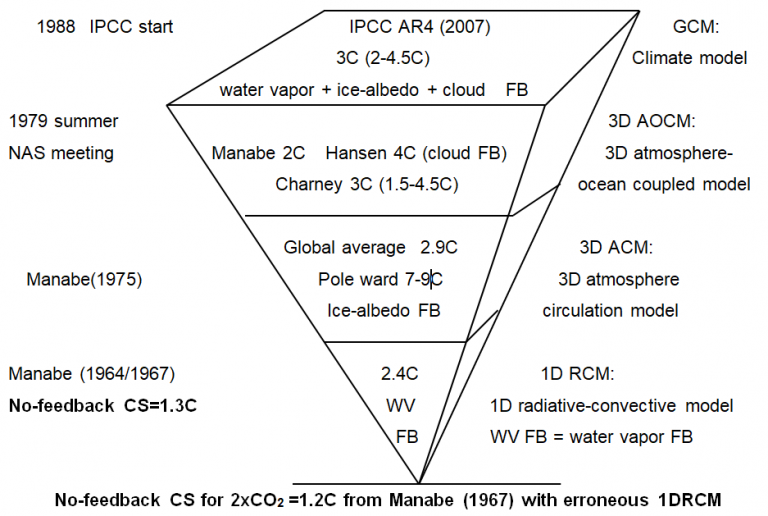

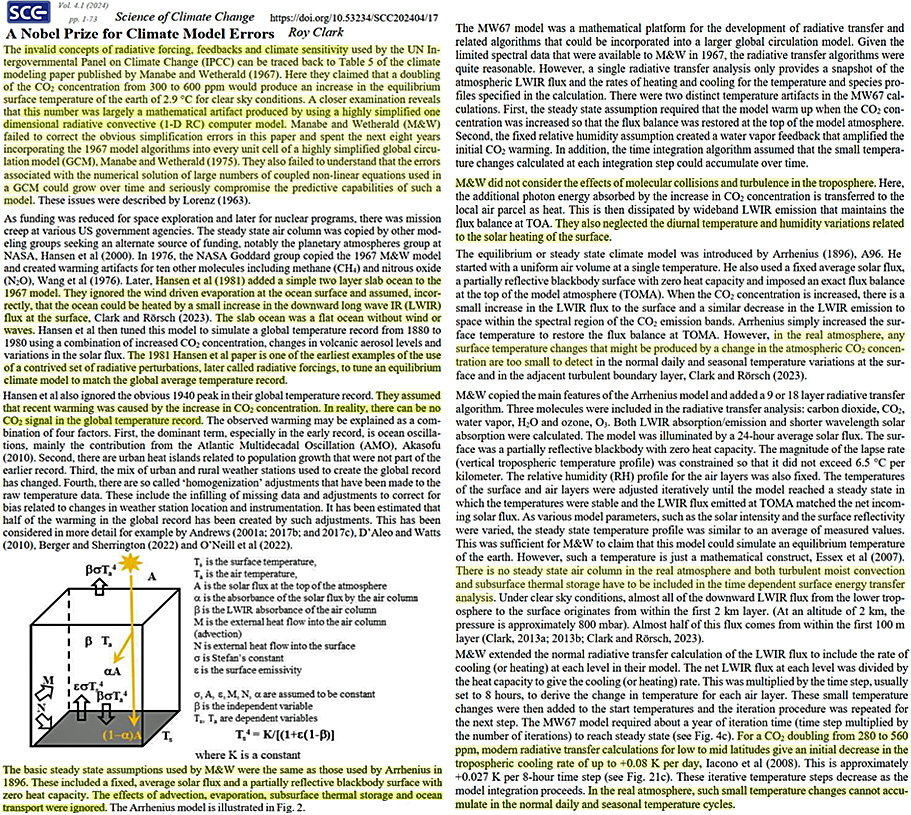

The anthropogenic global warming (AGW) scare was created in part by Japanese scientist Syukuro Manabe using a one dimensional radiative-convective model (1DRCM) having no ocean (1964/1967). He obtained a no-feedback climate sensitivity of 1.3°C for doubling of CO2 using the fixed lapse rate assumption of 6.5°C/km and a radiative forcing of 4(W/m2) at the tropopause, which was further enlarged to 2.4°C with a water vapor feedback.

Eminent meteorologist R. Newell from MIT criticized Manabe’s model lacking in ocean cooling. He obtained a No-feedback climate sensitivity of 0.03°C for a doubling of CO2 with a thermal inertia of 30 (W/m2) per 1°C for the surface waters of the ocean using a surface radiative forcing of 1(W/m2) to incorporate the IR spectra overlap between CO2 and water vapor.

Syukuro Manabe

The department of Energy & Dr. R. Cess, however, killed Newell’s ideas to promote nuclear reactors in a difficult time due to the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979.

Manabe continued his model studies to enlarge climate sensitivity (CS) for a doubling of CO2 with introducing various feed backs (FBs) as follows, which is the theoretical basis of IPCC’s AGW narrative.

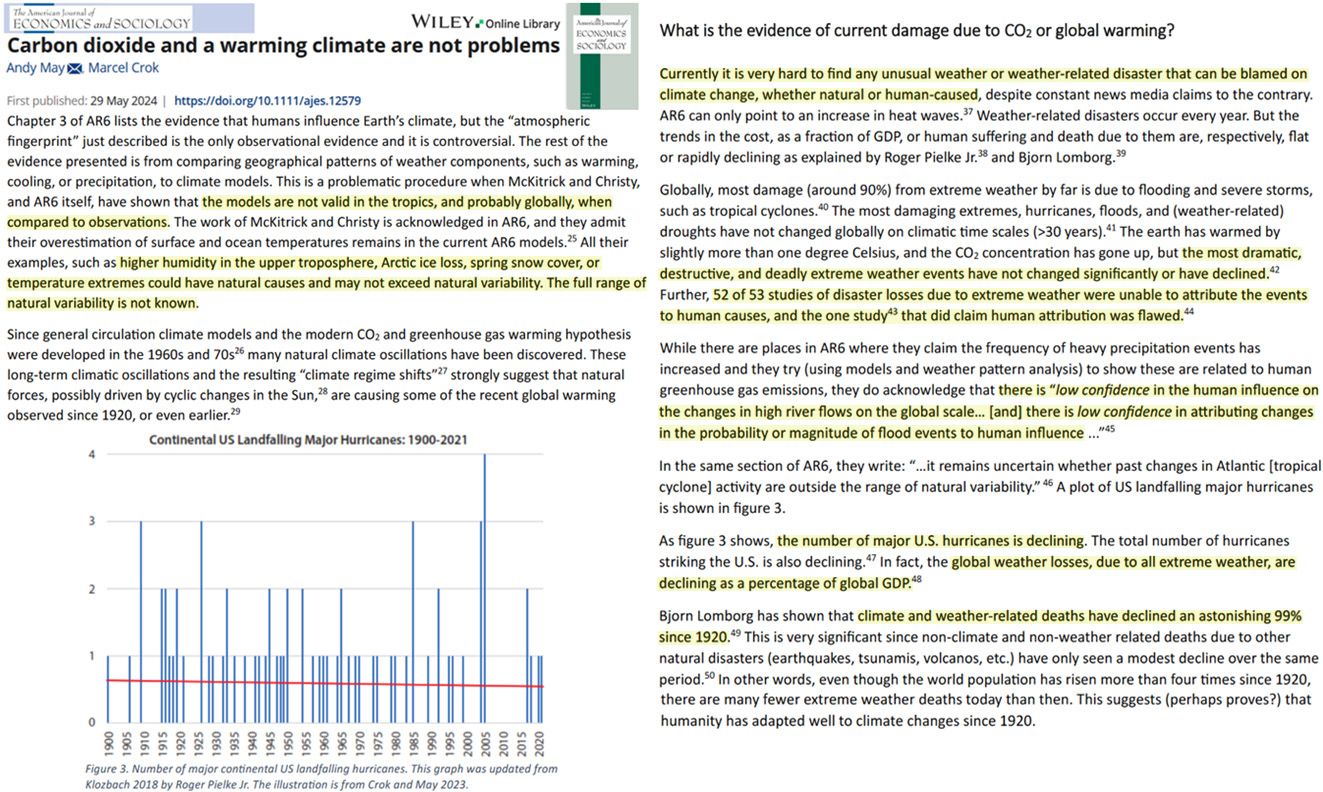

Fig. 1 History of the CS for 2xCO2 with model studies by Manabe & IPCC

Cess’s erroneous calculation of the Planck feedback parameter

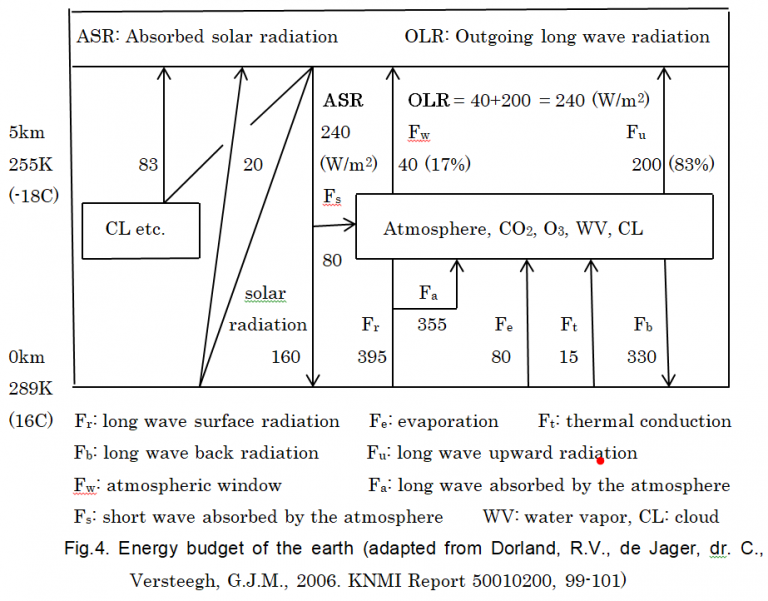

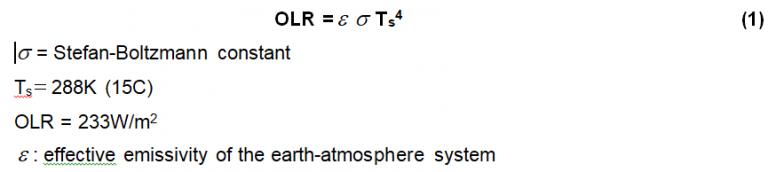

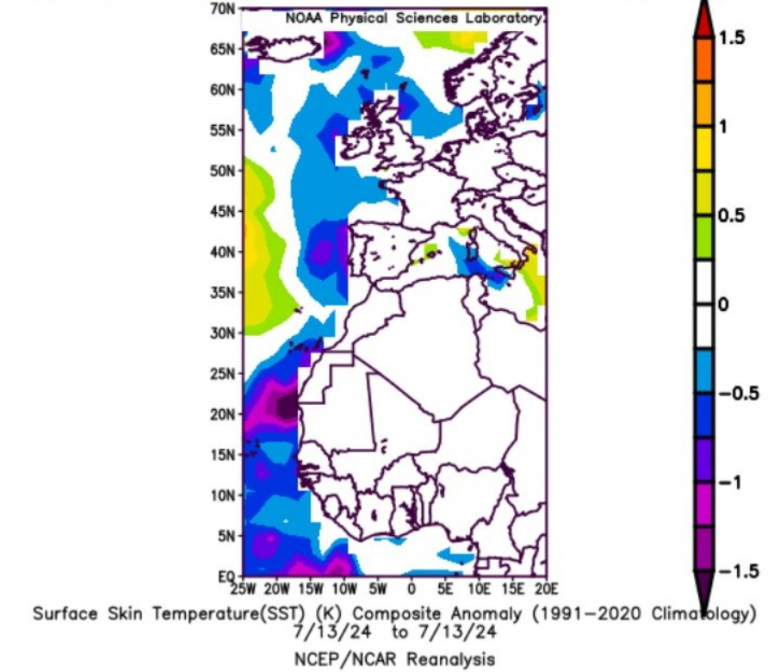

Cess (1976, 1989) expressed the outgoing long wave radiation (OLR) with equation (1) based on the old energy budget of the earth as shown by Fig. 2.

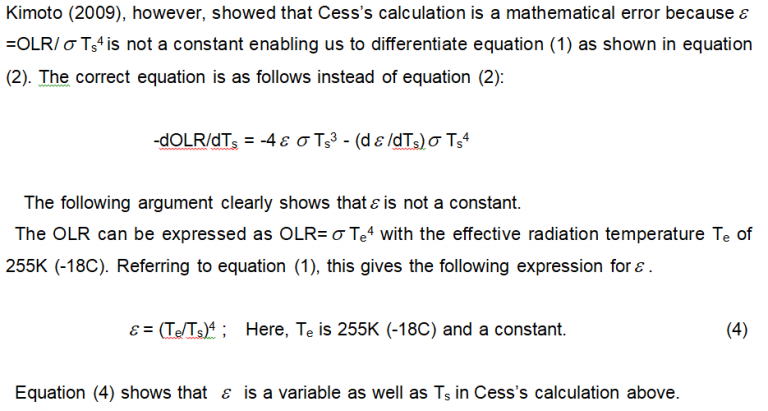

He obtained a Planck feedback parameter0 of -3.3(W/m2)/C with equation (2), giving a No-feedback CS of 1.2°C using a radiative forcing of 4W/m2 for a doubling of CO2 at the tropopause as follows:

Cess’s Planck feedback parameter is used in all GCMs for the IPCC ARs with a slight decrease of the radiative forcing from 4 (W/m2) to 3.7 (W/m2) for a doubling of CO2 by IPCC TAR (2000).

Fig. 3 Feedback parameters of 14 GCMs for the IPCC AR4 by Soden (2006)

Cess’s equation (1) is physically wrong

Cess did not know the atmospheric window because he was caught by the old energy budget of the earth (see Fig.2).

The OLR is expressed by equation (5) based on a modern energy budget of the earth as shown by Fig.4

OLR= Fu (Tu) (83%) + Fw (Ts) (17%) (5)

Equation (5) means the upper troposphere temperature Tu is increased as much as ~1°C with CO2 doubling instead of the surface temperature Ts.

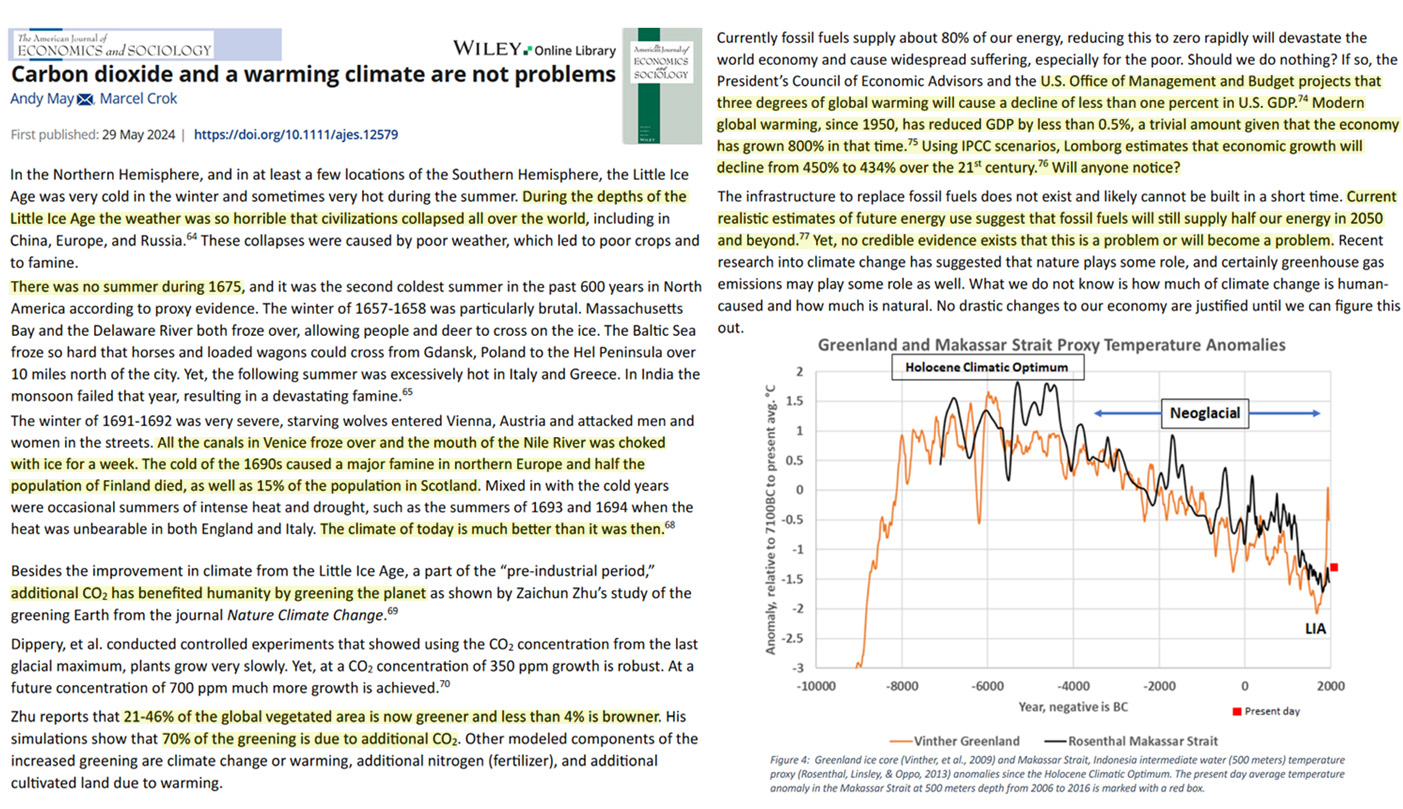

Comparison of no-feedback climate sensitivities

The following list shows the no-feedback climate sensitivities for a doubling of CO2 in the literature:

- Ramanathan (1979) 0.2°C based on the Stefan-Boltzmann law

- Newell (1979) 0.03°C based on the ocean thermal inertia of 30 (W/m2)/C

- Idso (1980) less than 0.26°C based on the natural experiments

- Ramanathan (1981) 0.17°C based on the Stefan-Boltzmann law

- Idso (1998) 0.1°C based on the 10 natural experiments

- Kimoto (2015) 0.15°C based on the Stefan-Boltzmann law

- Manabe (1964/1967) 1.3°C based on the 1DRCM having no ocean

- Cess (1976) 1.2°C based on a calculation with a mathematical error

- Hansen (1981) 1.2°C based on Manabe’s 1DRCM

- Schlesinger (1986) 1.3°C based on Manabe’s 1DRCM

- Schlesinger (1986) 1.2°C with a trick concealing Cess’s mathematical error

Conclusion

All green policy is nonsense because it depends on IPCC’s claim that the surface temperature Ts is increased as much as 3°C for CO2 doubling utilizing an erroneous Plank feedback parameter0 of -3.21(W/m2)/C from Cess’s mathematical error.

The Paris climate agreement reads as follows: “To keep the rise in mean global temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5°C.”

This is based on IPCC’s erroneous climate sensitivity of 3°C for doubling of CO2 discussed above. Therefore the Paris climate agreement is nonsense, though it governs the world politics now.

(References)

Cess, R.D., An appraisal of atmospheric feedback mechanisms employing zonal climatology, J. Atmospheric Sciences, 1976, 33, 1831-1843.

Cess, R.D., Potter, G.L., Blanchet, J.P., Boer, G.J., Ghan, S.J., Kiehl, J.T., Le Treut, H., Li, Z.X., Liang, X.Z., Mitchell, J.F.B., Morcrette, J.J., Randall, D.A., Riches, M.R., Roeckner, E., Schlese, U., Slingo, A., Taylor, K.E., Washington, W.M., Wetherald, R.T. and Yagai, I., Interpretation of cloud-climate feedback as produced by 14 atmospheric general circulation models, Science, 1989, 245, 513-516.

Hansen, J., Johnson, D., Lacis, A., Lebedeff, S., Lee, P., Rind, D. and Russell, G., Climate impact of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, Science 1981, 213, 957-966.

Idso, S. B., The climatological significance of a doubling of Earth’s atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration, Science 1980, 207,1462-1463.

Idso, S. B., CO2-induced global warming: a sceptic’s view of potential climate change,

Climate Research,1998, Vol.10, 69-82.

Kimoto, K., On the confusion of Planck feedback parameters, Energy & Environment, 2009, Vol.7, 1057-1066.

Kimoto, K., Will coal save Japan and the world?, Energy & Environment, 2015, 26, 1055~1067.

Manabe, S. and Strickler, R.F., Thermal equilibrium of the atmosphere with a convective adjustment, J. Atmospheric Sciences, 1964, 21, 361~385.

Manabe, S. and Wetherald, R.T., Thermal equilibrium of the atmosphere with a given distribution of relative humidity, J. Atmospheric Sciences, 1967, 24, 241-259.

Manabe, S and Wetherald, R.T., The effects of doubling the CO2 concentration on the climate of a general circulation model, J. Atmospheric Sciences, 1975, 32, 3~15.

Newell, R.E. and Dopplick, T.G., Questions concerning the possible influence of anthropogenic CO2 on atmospheric temperature, J. Applied Meteorology, 1979, 18, 822-825.

Ramanathan, V., et al., J. Geophysical Research, 84, 4949-4958 (1979)

Ramanathan, V., The role of ocean-atmosphere interactions in the CO2 climate problem, J. Atmospheric Sciences, 1981, 38, 918-930.

Ramanathan, V., The role of earth radiation budget studies in climate and general circulation research, J. Geophysical Research,1987, 92, 4075-4095.

Schlesinger, M.E., Equilibrium and transient climatic warming induced by increased atmospheric CO2, Climate Dynamics, 1986, 1, 35-51.

Soden, B.J. and Held, I.M., An assessment of climate feedbacks in coupled ocean-atmosphere models. J. Climate, 2006, 19, 3354-3360.

Recent Comments