An assessment of the 1856-2012 drought frequency/intensity along the US West Coast leaves no role for human activity in hydroclimate.

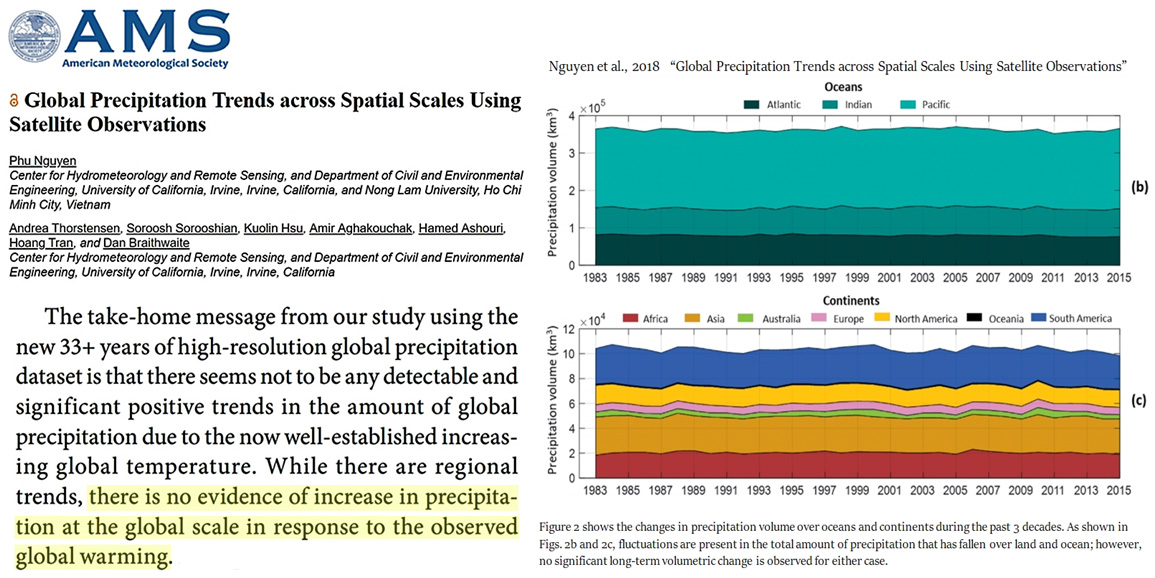

Across the globe, no clear precipitation trends have been observed in the last several decades (Nguyen et al., 2018)

Image Source: Nguyen et al., 2018

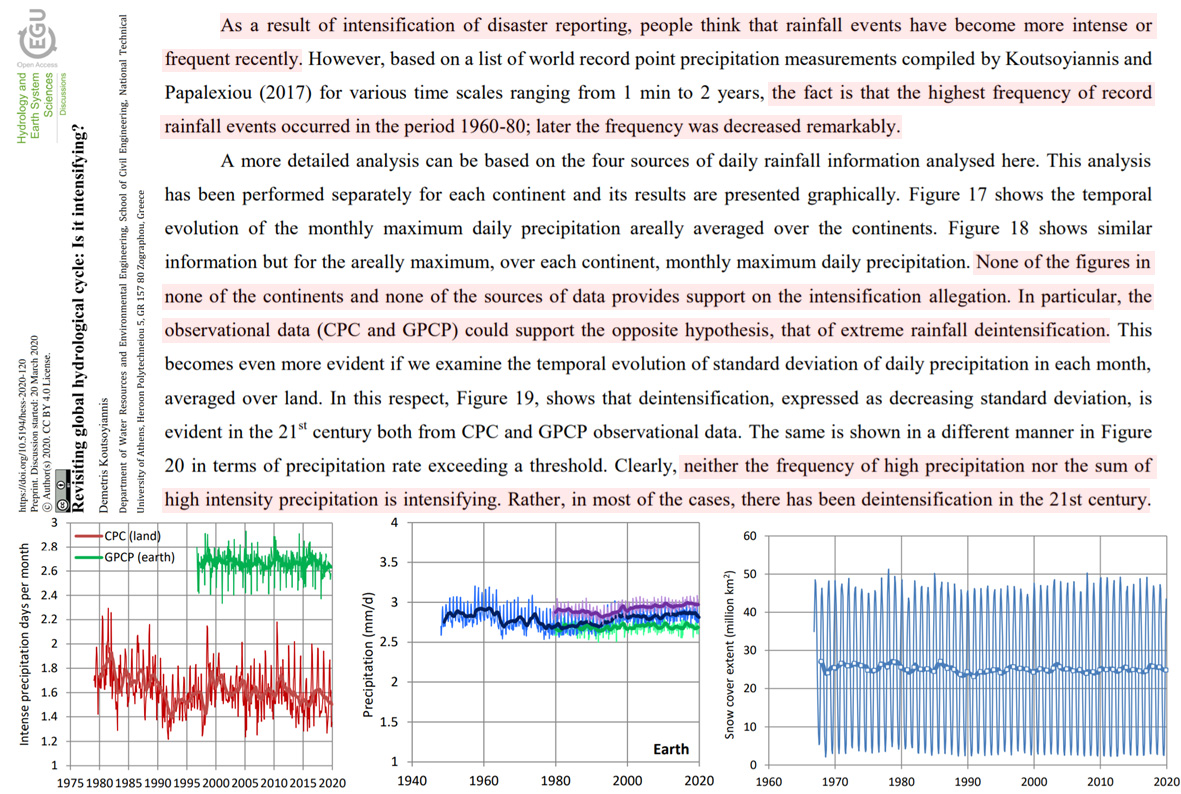

Instead of an intensification of the hydrological cycle projected by climate models (i.e., more droughts, floods, and extreme rainfall events), satellite data suggest extreme precipitation has actually de-intensified globally (Koutsoyiannis, 2020).

Image Source: Koutsoyiannis, 2020

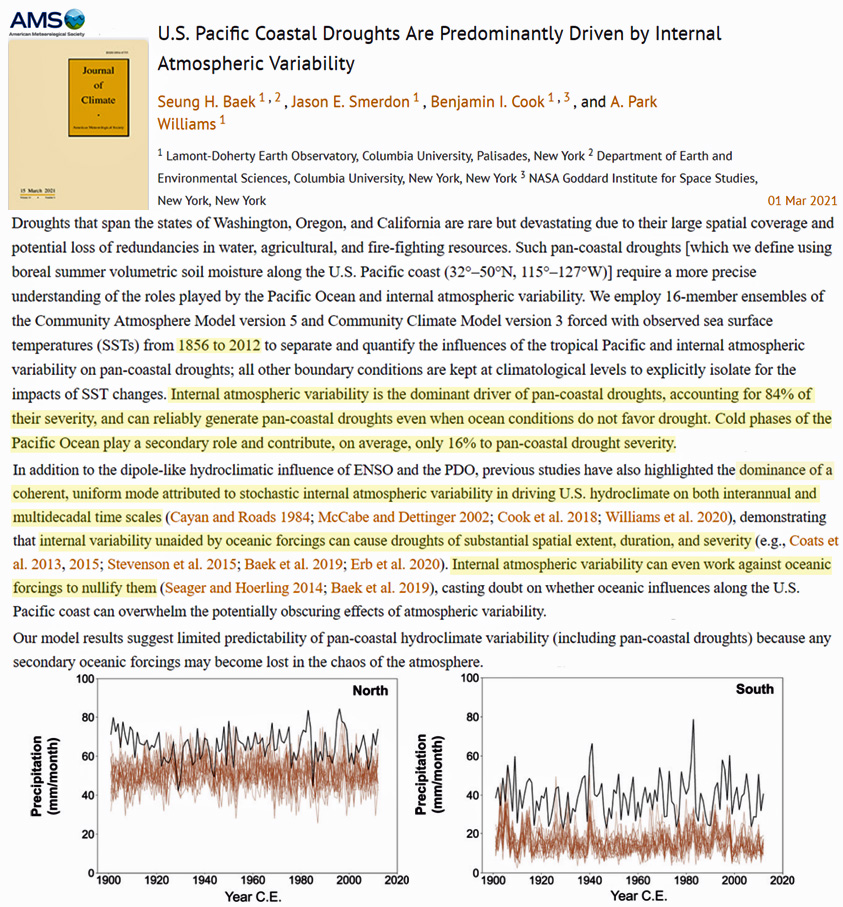

It should therefore not be surprising that a new study of precipitation patterns along the Western coast of the United States finds random internal variability dominates (84%) as the driver of large-scale droughts for this region (Baek et al., 2021).

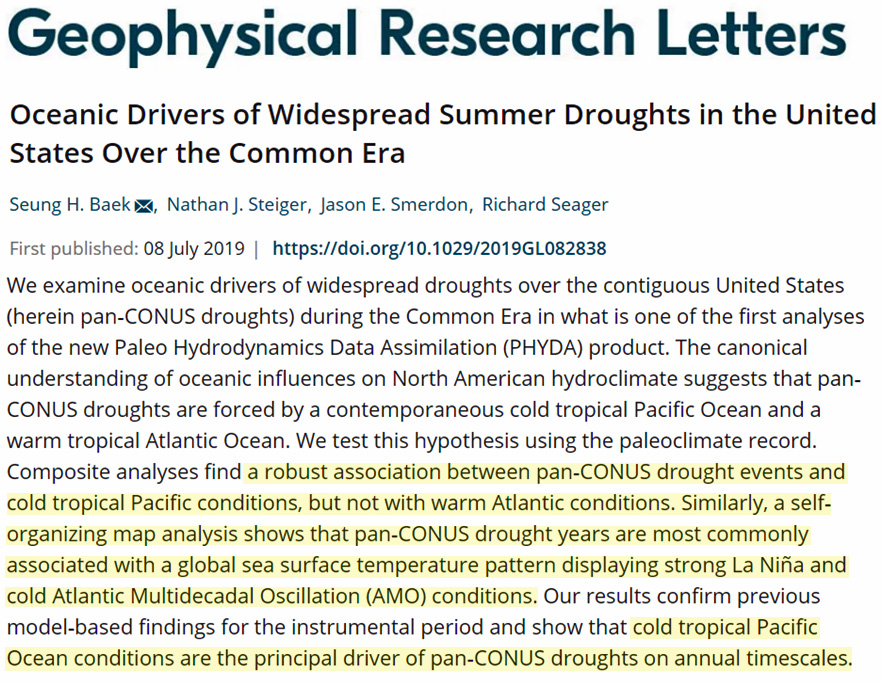

If there is any role for surface temperature changes contributing to the worsening of droughts, it’s opposite the global warming narrative; 16% of pan-coastal drought is attributed to cooling ocean waters (Baek et al., 2019 and Baek et al., 2021).

Image Source: Baek et al., 2021

Image Source: Baek et al., 2019

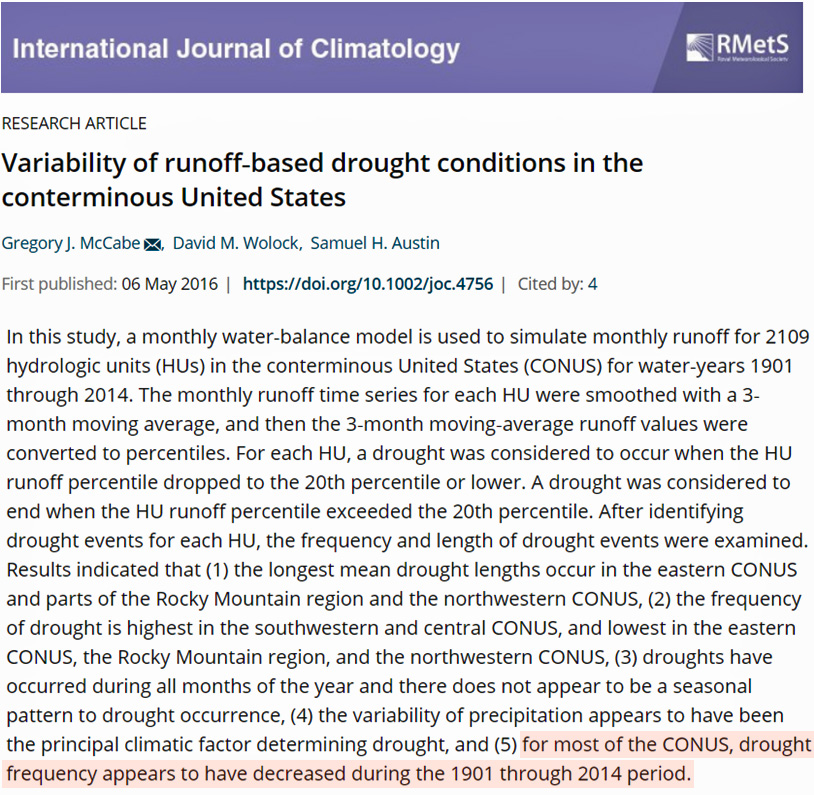

Drought frequency across the continental United States has been on a declining trend since 1901 (McCabe et al., 2017).

Image Source: McCabe et al., 2017

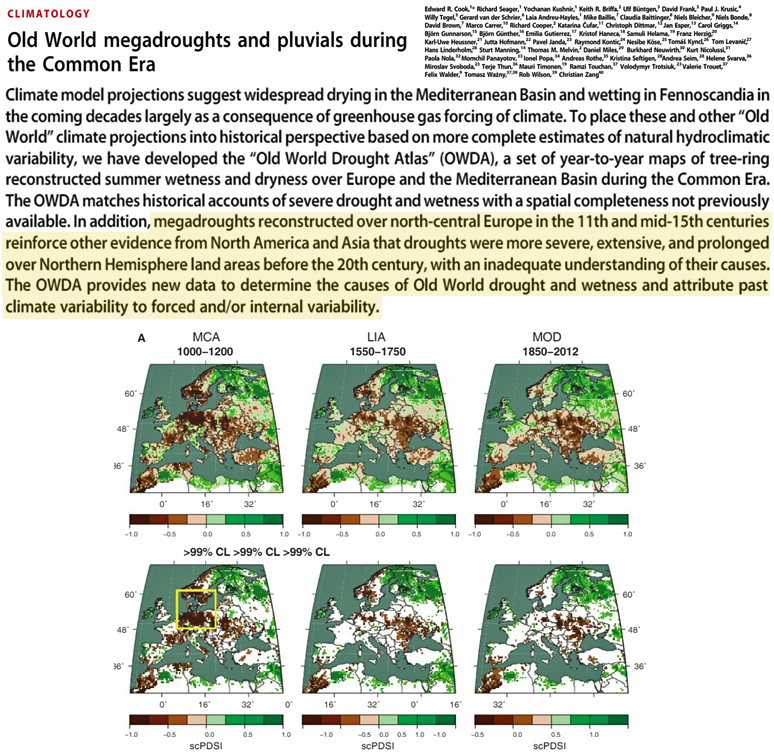

And if we consider the Northern Hemisphere as a whole, droughts “were more severe, extensive, and prolonged over Northern Hemisphere land areas before the 20th century” (Cook et al., 2015). Put another way, megadroughts have become far less common ever since the dramatic uptick in fossil fuel burning began in the 20th century.

In 2004 McCabe et al published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences their research on the drought patterns in the contiguous United States during the last century.

They concluded that more than half of the drought patterns were explained by the phases of the PDO and AMO.

In June, 2012 Roger Pielke, Sr. referenced that research, which was referenced by Judith Curry the previous year at a NOAA workshop on water, in a blog article noting the similarity between the then current drought patterns in the U.S. and the drought patterns which existed in the 1950s when the ocean cycles were in the similar positions.

As Pielke, Sr. pointed out then, which is true today, the drought patterns are not unprecedented, they have happened before.

https://pielkeclimatesci.wordpress.com/2012/06/27/perspective-on-the-hot-and-dry-continental-usa-for-2012-based-on-the-research-of-judy-curry-and-of-mccabe-et-al-2012/

Thanks for this supplement

A possible confounding factor is the intensity of irrigation in the Great Plains. When it is hot and dry they irrigate, which cools things down and reduces the intense thermals that produce thunder storms.

That’s an interesting theory I had not considered before. As someone who lives in the great plains (Kansas), I can confirm that irrigation is dropping due to a switch to less water-intensive crops or by converting crops to pastures. The Ogallala Aquifer can’t continue to support a high level of pumping; farmers are being forced to adapt. If your theory is correct, thunderstorms should be increasing.

YIPES!

I was not aware of that. Thanks.

Looking for what might be a credible objective source on it I came up with this…

https://www.mining.com/web/mining-the-ogallala/

If you have any, they’d be nice to have.

I would need to see some better calculation of the contribution of Pacific cooling to the drought – the cooling clearly leads to less evaporation. I can’t believe this effect is quite so small in relation to “natural variability”

[…] New Study: Drought In Western US Is 84% Driven By Internal Variability And 16% By Ocean Cooling […]

[…] Siehe auch Bericht auf Notrickszone. […]